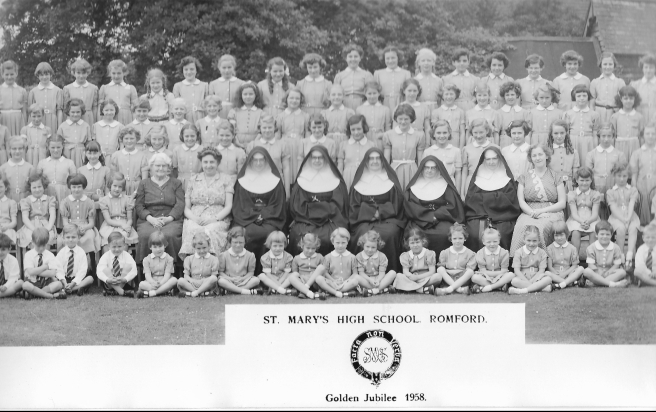

A Flap of Nuns isn’t the title of a book on my bookshelf. The term is one of the collective nouns in James Lipton’s classic An Exaltation of Larks. I use it here as a means of confession that I own far too many books about nuns than you would expect of a lapsed Catholic and firm agnostic. But once a convent schoolgirl always a convent schoolgirl in some sense. I was educated by nuns from the age of seven to eighteen, first at St. Mary’s Convent in Romford and then at Brentwood Ursuline Convent High School. If it were up to me the collective noun for nuns would not be Flap, it would be Clack, for the distinctive sound of rosary beads, worn hanging from the waist, rattling and clacking as the nuns walked. It was a sound that could strike fear into the heart of a schoolgirl who wasn’t where she was supposed to be, but it also served as a useful warning of a nun’s approach. It is a sound I have never forgotten, the background soundtrack of my daily life for so long.

I remember the nuns of St. Mary’s fondly; for the most part they were kindly and nurturing. Most memorable was Sister Gertrude, a tiny bent old woman who did all the shopping for the convent. My mother often saw her toiling through Romford Market carrying a clutch of enormous bulging shopping bags. Brentwood Ursuline was a more complex world. For a start there were far more nuns to deal with and some of them could be harsh. Sister Pauline was another tiny woman but she was a tyrant. One day standing in line to go into the refectory for lunch I began to feel faint. Sister Pauline stood watch and I asked if I could go to the health room, it was my time of the month and I felt faint. “Nonsense girl, don’t make such a fuss” was her response. If nuns had to repress the femininity of their bodies then so should we was the underlying message. Within moments I passed out at her feet and had to be carried to the health room. Ever after she seemed to pick on me. She was our needlework teacher, a class I hated. I worked as slowly as possible embroidering the daffodils on my tablecloth, a silent form of rebellion. Each year the girls in the class began a new project while I continued with my daffodils. After seven years it was the only thing I had completed. I still have it, buried at the bottom of a linen drawer.

The Brentwood nuns were divided by a distinct class system. There were the teaching nuns, many of whom had been pupils at the school, and beneath them the worker nuns who did all the drudgery of cooking and cleaning, most of them from Ireland. Our headmistress, Mother Joseph, was rumored to be an aristocrat who would have had the title Lady in secular life. She was remote and haughty and quite terrifying. But I revered my history teacher, Sister Dolores, whose classes inspired me to study history at university. She was a scholar working on a book about the Benedictine monastery of Cluny under the eleventh century abbot St. Hugh. She was a wonderful teacher but often seemed troubled and distracted. We soon learned why. The year after I left school she left the convent and eventually published the book under her name in the world, Noreen Hunt. Along with speculation about which nuns might leave and which were secret lesbians were whispered rumors of particular girls being groomed for the religious life. Girls who visited the chapel before classes began in the morning or recited prayers with noticeable fervor were said to be showing signs of having a vocation. Each September when school began we were alert for sightings of former pupils in the chapel wearing the garb of postulants. The year I left school two of my closest friends entered the convent. One was a nun for twenty years before leaving while the other eventually became the Reverend Mother.

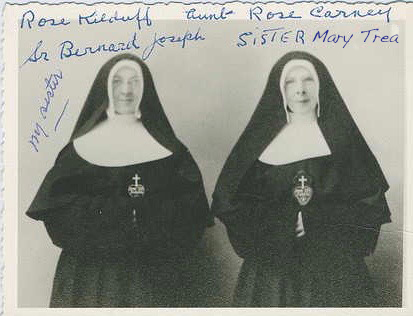

I also had nuns in the family. My father’s cousin and an aunt were both nuns. We often visited his cousin Sister Bernard Joseph at her convent in Lancashire and we received regular letters from his aunt Sister Trea. My father read them aloud to the family, commenting that they were like the mystical writings of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux. My Irish grandmother, who lived with us, had supposedly also wanted to be a nun but her family could not afford a second dowry. They had paid a dowry to the convent for her elder sister Rose, who became Sister Trea. My grandmother’s bedroom was like a little chapel, the walls covered with religious images, a flaming Sacred Heart picture, a frighteningly realistic bloody crucifix. In the morning before leaving for school we would kneel at her bedside to say our prayers. Then she gave us each a mint, holding the white circle of candy before us almost like the host at mass. Eventually my grandmother came close to her wish. When the bustle of family life became too much for her delicate nerves she retired to a convent home for the elderly.

No surprise, then, that I’ve always been drawn to reading about nuns, to probe the essential mystery of who these women really are beneath the obscuring habits and bland expressions. What really drew them to convent life, a genuine desire for a life of prayer or a need to escape their circumstances in the world? What inner turmoil must they suppress to keep on the hard path they have chosen? What dramas play out behind the convent walls? Fortunately the pages of history have some fascinating answers to these questions and there is plenty of drama to be found. Here are some of the stories on my bookshelves.

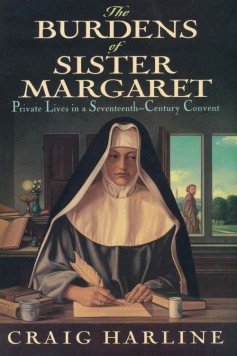

The Burdens of Sister Margaret: Private Lives in a Seventeenth Century Convent by Craig Harline is the story of Margaret Smulders, a nun in Leuven, Flanders, who accused a chaplain of sexually harassing her and in turn was accused of being possessed by demons. She spent years exiled to a room above the convent gatehouse writing voluminous letters to the bishop pleading her case and spreading gossip about her fellow nuns. Among Sister Margaret’s complaints was that the nuns spent too much time cooking waffles to give to the influential people of the town instead of praying! The bishop was also the recipient of letters from the other nuns detailing their complaints against Margaret. Harline was actually researching quite another subject when he came upon this cache of letters among the bishop’s papers and was hooked. From the stew of gossip and innuendo he reveals an intimate portrait of the daily life and trials of one convent.

The Burdens of Sister Margaret: Private Lives in a Seventeenth Century Convent by Craig Harline is the story of Margaret Smulders, a nun in Leuven, Flanders, who accused a chaplain of sexually harassing her and in turn was accused of being possessed by demons. She spent years exiled to a room above the convent gatehouse writing voluminous letters to the bishop pleading her case and spreading gossip about her fellow nuns. Among Sister Margaret’s complaints was that the nuns spent too much time cooking waffles to give to the influential people of the town instead of praying! The bishop was also the recipient of letters from the other nuns detailing their complaints against Margaret. Harline was actually researching quite another subject when he came upon this cache of letters among the bishop’s papers and was hooked. From the stew of gossip and innuendo he reveals an intimate portrait of the daily life and trials of one convent.

Virgins of Venice: Broken Vows and Cloistered Lives in the Renaissance Convent by Mary Laven is another portrait of a community where religious motivations didn’t always predominate. Many women in this period did not go willingly into convent life, but were forced there by their families for a variety of motives, financial being uppermost. It is not surprising then that they often failed to live up to their vows of celibacy and poverty. This Venetian convent was a hotbed of illicit affairs and conspicuous consumption as life within the walls mirrored the political scheming in the city state without.

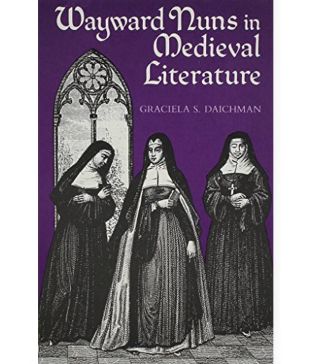

The true to life figure of the unhappy and rebellious nun made her way into medieval and renaissance literature as Graciela Daichman explores in Wayward Nuns in Medieval Literature. From Chaucer’s Madame Eglentyne on, the wayward nun was a common satirical character in literature and song, often heard bemoaning her fate. As Daichman explains: “the bitter and the wanton mingle in the nun’s complaint; the resentment and the pent up desire to share once again in the life outside the convent walls becomes intolerable.” Here is one typical French chanson:

Alas, if I had married

Or had a courtly lover –

But I became a nun

A nun to my lasting sorrow

And great the sin

Of those who put me here

May God’s wrath do them in!

For if I had ever known

I’d never have gone in!

Some particularly wayward nuns feature in Craig Monson’s Habitual Offenders: A True Tale of Nuns, Prostitutes, and Murderers in Seventeenth-Century Italy. The setting is a convent in Bologna founded for reformed prostitutes, who needless to say did not make the best candidates for a cloistered life. Two of the sisters spent most of their time flirting at the grille with visiting soldiers. One day the two disappeared causing a scandal in the town, but when their garroted bodies were discovered in a wine cellar the case blew up to involve even the Pope’s attention. The investigation and trial that followed make for a gripping true crime read.

Sylvia Townsend Warner’s 1948 novel The Corner That Held Them may begin with a gruesome murder, but it is as an indelible portrait of the small daily affairs of life in a fourteenth century convent that the book excels. At the Benedictine convent of Oby in Norfolk the nuns experience an outbreak of the plague, the fall of the church spire, the mysterious disappearance of an embroidered altar cloth, and the ongoing mystery of their priest Sir Ralph’s true identity. As the isolated community experiences rivalries over the position of Prioress and anxiety over the bishop’s visitations, developments in the outside world are glimpsed: a new style of narrative poetry and the new polyphonic Church music are heard as some of the characters travel beyond the convent walls. Townsend Warner casts a spell, immersing the reader completely in a small corner of a distant world.

Sylvia Townsend Warner’s 1948 novel The Corner That Held Them may begin with a gruesome murder, but it is as an indelible portrait of the small daily affairs of life in a fourteenth century convent that the book excels. At the Benedictine convent of Oby in Norfolk the nuns experience an outbreak of the plague, the fall of the church spire, the mysterious disappearance of an embroidered altar cloth, and the ongoing mystery of their priest Sir Ralph’s true identity. As the isolated community experiences rivalries over the position of Prioress and anxiety over the bishop’s visitations, developments in the outside world are glimpsed: a new style of narrative poetry and the new polyphonic Church music are heard as some of the characters travel beyond the convent walls. Townsend Warner casts a spell, immersing the reader completely in a small corner of a distant world.

Finally, I must confess to a guilty pleasure. There is no saving grace of literary merit in Orana Papazoglou’s Sanctity, but it was tremendous fun to read. From the outset the reader knows that one of four young women who enter a convent together as postulants will ultimately commit murder. The breathless narrative keeps you guessing with plenty of clues and red herrings scattered along the way. Here are all the tropes of convent life from excessive religiosity and mystical visions to madness and repressed lesbian longings. At this point I don’t remember “who done it” so I just might have to read it again!

Great article Rita…I think there’s a book in this for you to write!

LikeLike