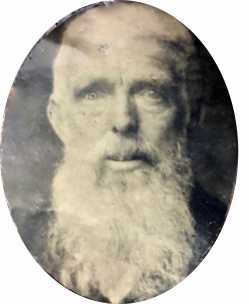

The newspaper clipping is yellowed with age but carefully folded and preserved in a box of papers left by my Irish grandmother. The box was inside a larger one with an assortment of family papers that sat in the back of my closet for more than two decades. I would have opened it far sooner if I had known all the little treasures and poignant stories held within: my father’s British Army ID card, congratulations telegrams sent to my parents on their wedding day in 1947, my Flemish grandmother’s passport stamped with all her visits to England when I was small, annual receipts my Irish grandmother kept for the upkeep of the grave of the baby she lost to pneumonia before my father was born. The yellowed newspaper clipping my grandmother kept so carefully all her life was the announcement of her father Hugh Carney’s death in 1913.

It was just last year, preparing for my first visit to Ireland, that I learned the identity of my great-grandparents. My grandmother never spoke about Ireland or her family. All I knew was her maiden name and that she and my grandfather both came from Knock in County Mayo in the west of Ireland. But through the wonders of online genealogical research I was able to discover my entire family tree. By the time I drove into Knock I had a map of the Old Cemetery marked with the locations of my great-grandparents’ graves. But if only I had opened that box first and found the newspaper clipping I would have saved a lot of research time. The announcement lists the names and relationships of all the extended family who attended the funeral service. There is my grandmother’s name, Bridget, daughter.

The language of the announcement is lovely, the cadence magisterial and dignified like the prose of a nineteenth century novel:

“Amid many manifestations of deep and sincere regret the remains of the above named much esteemed deceased were laid to rest in Knock cemetery Monday 20th October…fortified and consoled by the ministrations of God’s Holy Church and perfectly resigned to the will of His Divine Master he breathed his last on the morning of Saturday 18th October, surrounded by all those who were nearest and dearest to him on earth…his death was happy, peaceful, and holy and edifying as his life. An honest, upright, and devout Christian, a model husband and father, and a kindly and charitable neighbour, we pray that his long last sleep be calm and peaceful and that his awakening shall be immortal and glorious…The interment took place immediately after Mass and was attended by an immense concourse of people. The adjoining parishes and towns, as well as his own native parish of Knock were largely represented, and afforded incontestable evidence of the widespread regard and high esteem entertained for deceased and the members of his family.”

My grandmother went on to endure a troubled, unhappy marriage and was eventually left alone to raise her youngest son, my father. So the phrase “model husband and father” jumps out at me. Hugh Carney was evidently that ideal and it is a measure of his youngest daughter’s devotion that she kept this account of his death with her for the rest of her long life.

I was thrilled to find this lost piece of family history, but when I turned the clipping over to see if there was some clue to the name of the newspaper, I found so much more. A court report that reads like a little gem of a short story or one-act play that could have come from the pen of one of Ireland’s classic authors. Headlined A Title Case, it concerns a dispute over the ownership of a piece of bogland, giving us a glimpse into traditional Irish rural life.

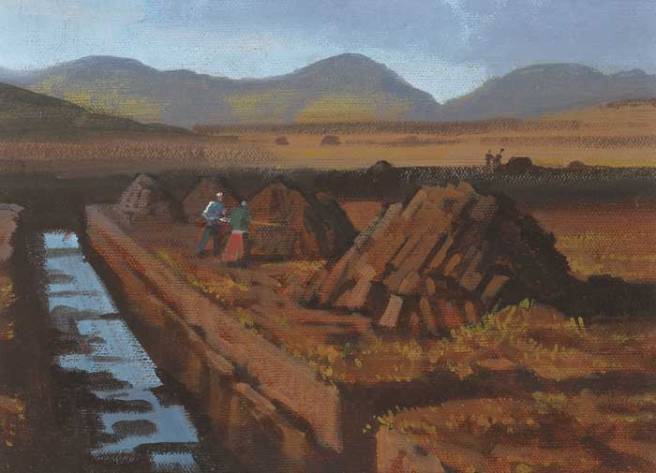

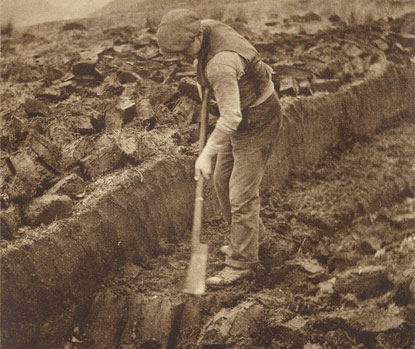

The ownership of a piece of bog was no small matter for the peat or turf that Irish farmers dug out was their sole source of fuel for heating and cooking. Formed of dead and decaying vegetation in wet spongey earth unsuitable for agriculture, the peat was cut and piled to dry, the stacks a familiar sight in the Irish countryside. The burning peat slices gave a distinctive sweet smell to the smoke wafting from cottage chimneys.

The ancient rights of turbary, the right to cut turf from a particular area of bog, were jealousy guarded. So John Blowick of Belcarra sued John Carney and his son James of Elmhall (no relations as far as I know) to recover five pounds damages for trespassing on his bog. The report continues:

“Mr. Verdon for the plaintiff.

Mr. H. P. Howdy defended.

Mr. M. Moran, C.E. produced a map of the locus in quo on behalf of the plaintiff.

Mr. Blowick was examined and said the defendants commenced cutting turf on his bog on the 15th July. Witness paid rent for this bog and always used it.”

There follows some confusing and contradictory testimony. Two witnesses stated they had never seen the Carneys cutting turf on that piece of bog, Mr. Blowick was the only one who ever used it. But when it came time for the defendant to testify:

“John Carney said he had two holdings at Belcarra and he had a right to turbary attached to them. The landlord’s agent pointed him out the place to cut his turf, and he had been using the bog in dispute for the past 45 years.”

Hmm. He claimed he had been cutting turf there for 45 years but two witnesses had never seen him there in all that time. Then another character is introduced, one Edward Loftus.

“Loftus said he had a portion of this bog and gave up his portion to Mr. Blowick. Carney had another portion of this particular bog and always used it and Blowick had never any rights on it.”

Things are becoming tangled indeed. Another witness, James Heneghan, said he saw the Carneys cutting turf on this bog for the past 35 years. Then we hear from Mr. George H. Garvey, Assistant County Surveyor, who could perhaps be considered an expert witness. But instead of relating his testimony, the report states cryptically “he proved a man of the place for the defence.”

More contradictions follow:

“ Mr. Blowick was recalled and in reply to his Honor denied that Loftus ever gave him up a strip of bog.”

If the reader is confused, then so too was the judge. In fact he just threw up his hands. The report concludes:

“His Honor said he could not make up his mind that Blowick had established his claim to the place, and he would dismiss the case without prejudice He allowed 30s expenses.”

It’s like a Waiting for Godot set in a bog in which Vladimir and Estragon are replaced by Irish tenant famers all talking at cross purposes, truth as slippery as the peaty mud at their feet. And the English authorities unable to make any sense of it all. A fine metaphor for what would happen in Ireland in the decade following 1913.

I never spoke to my Irish grandmother about anything important when I was growing up. She was a quiet, sad old lady who spent a lot of time praying the rosary. Now I wish I could thank her for leaving this flimsy little slip of newspaper that carried tales of death and life into the future for me to find.

With special thanks to Geraldine Gibbons of Drumcliffe who took us to Knock.

Experience the best of Irish landscape and culture with Wild West Irish Tours.

Our great grandmother, Rachel Mary Gilmore, told us that we had no idea what Real Work entailed. First on her long list of heavy chores was the periodic task assigned to her and her sister, Ruth, to collect and trundle the peat from the bog to the cottage in north Armagh. Market and fair days, which involved at least as much carting to and fro by shank’s mare, at least had the reward of social connection. Lovely blog article. cheers

LikeLike