On My Bookshelf I find a favorite history book about a very strange painting…

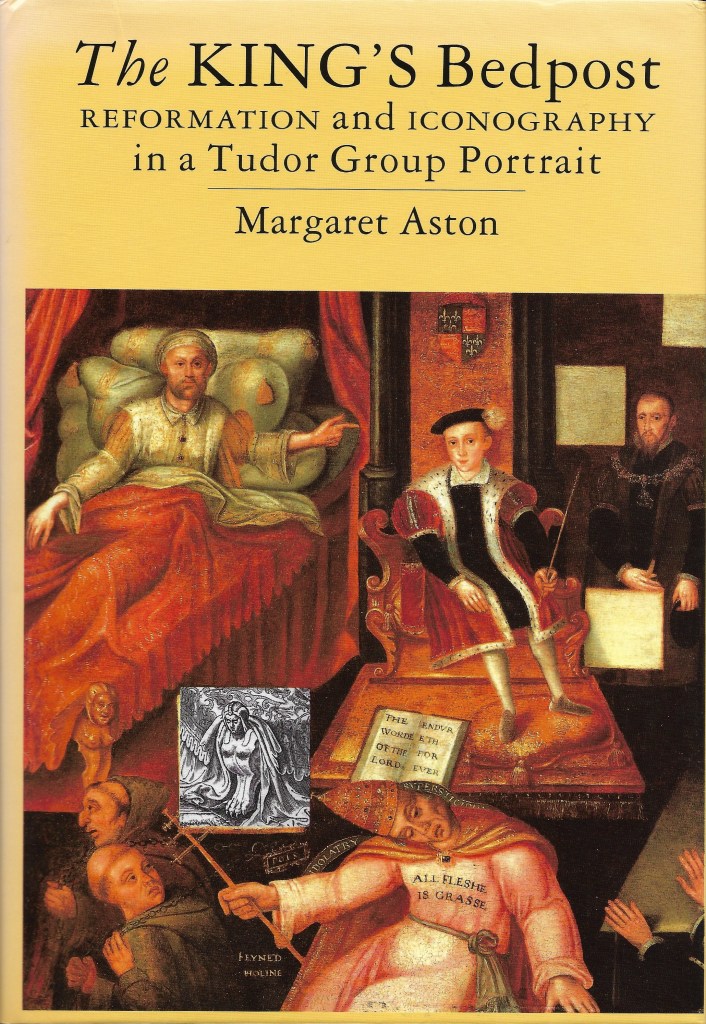

At first glance, maybe even a second or third, this is a mess of a painting. It’s busy with awkwardly positioned figures and decorative elements; there’s nowhere for the eye to rest. The viewer’s eye darts about the various unrelated parts trying to make sense of it all. Then there are the blank squares and the puzzling scene in the upper right, a picture within a picture. The artist is obviously trying to say something, but what?

As Margaret Aston explains in The King’s Bedpost it is best to think of it, not as a painting, but as a comic strip or political cartoon. The blank squares were intended to hold text, just like the speech bubbles of today. For unknown reasons they were not all filled in. The book turns that old saying, a picture is worth a thousand words, on its head, for it takes many thousands of words to explain this one. The painting may be no masterpiece but, Aston says, “undistinguished art can make interesting history.”

Explaining the painting takes us on a journey through the Old Testament Kings, sixteenth century Dutch art, crucial decades of the English Reformation when much of the medieval heritage of religious art was destroyed by iconoclastic reformers, and even into Elizabeth I’s private chapel. The painting is visual propaganda for the reformers’ view that all religious images and devotional objects were “Popish abominations” akin to pagan idolatry. Once thought to have been painted during the reign of the boy King Edward VI, seen seated in his Chair of State mounted on a dais, Aston shows that it actually reflects the religious conflicts and anxieties of Elizabeth I’s reign. She also details evidence that the source materials for the painting date to the 1570’s. For the unknown artist’s skills were limited, note the unconvincing size and position of the hands, so he copied much of the painting from other works. This dating is confirmed by the modern science of dendrochronological analysis; the wood panel comes from a tree that was cut down between 1574 and 1590.

Aston begins by identifying the people in the painting, recognizable because they are copies of portraits by various artists produced in the 1560’s and 70’s.. She draws our attention to a horizontal line following the base of the king’s dais dividing the painting into upper and lower sections, upper being good and lower bad. Fashion also divides the groups. In the lower section several of the men sport tonsures, the monastic hair style, branding them as Catholics. In the upper section there are no tonsures but copious beards, the style favored by the Protestant reformers.

Continue reading “The King’s Bedpost”