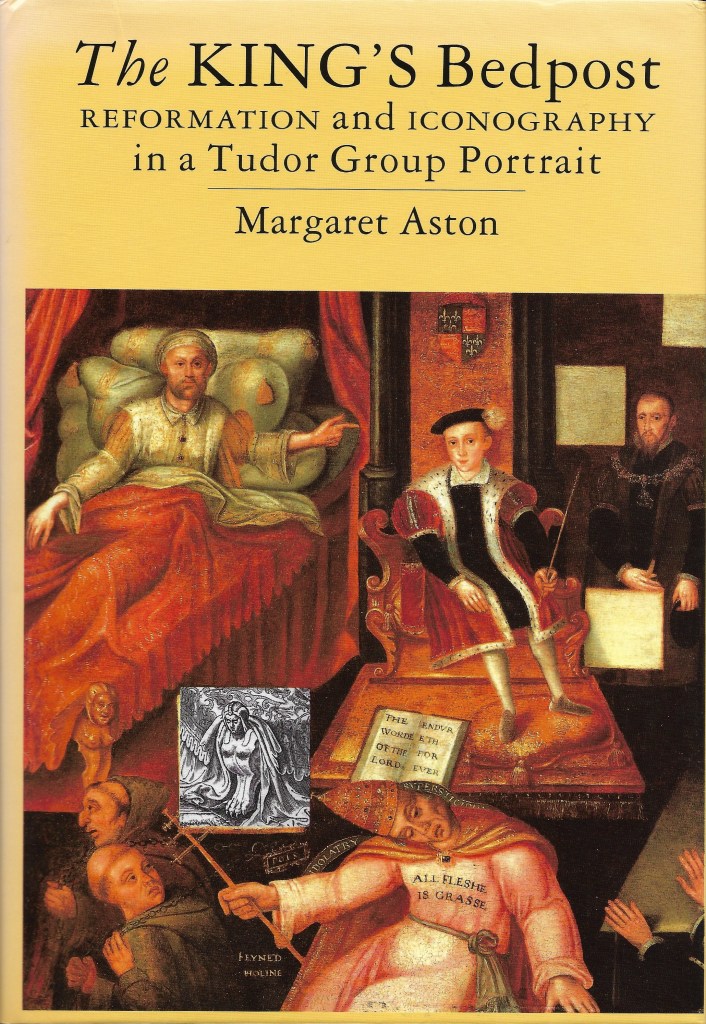

On My Bookshelf I find a favorite history book about a very strange painting…

At first glance, maybe even a second or third, this is a mess of a painting. It’s busy with awkwardly positioned figures and decorative elements; there’s nowhere for the eye to rest. The viewer’s eye darts about the various unrelated parts trying to make sense of it all. Then there are the blank squares and the puzzling scene in the upper right, a picture within a picture. The artist is obviously trying to say something, but what?

As Margaret Aston explains in The King’s Bedpost it is best to think of it, not as a painting, but as a comic strip or political cartoon. The blank squares were intended to hold text, just like the speech bubbles of today. For unknown reasons they were not all filled in. The book turns that old saying, a picture is worth a thousand words, on its head, for it takes many thousands of words to explain this one. The painting may be no masterpiece but, Aston says, “undistinguished art can make interesting history.”

Explaining the painting takes us on a journey through the Old Testament Kings, sixteenth century Dutch art, crucial decades of the English Reformation when much of the medieval heritage of religious art was destroyed by iconoclastic reformers, and even into Elizabeth I’s private chapel. The painting is visual propaganda for the reformers’ view that all religious images and devotional objects were “Popish abominations” akin to pagan idolatry. Once thought to have been painted during the reign of the boy King Edward VI, seen seated in his Chair of State mounted on a dais, Aston shows that it actually reflects the religious conflicts and anxieties of Elizabeth I’s reign. She also details evidence that the source materials for the painting date to the 1570’s. For the unknown artist’s skills were limited, note the unconvincing size and position of the hands, so he copied much of the painting from other works. This dating is confirmed by the modern science of dendrochronological analysis; the wood panel comes from a tree that was cut down between 1574 and 1590.

Aston begins by identifying the people in the painting, recognizable because they are copies of portraits by various artists produced in the 1560’s and 70’s.. She draws our attention to a horizontal line following the base of the king’s dais dividing the painting into upper and lower sections, upper being good and lower bad. Fashion also divides the groups. In the lower section several of the men sport tonsures, the monastic hair style, branding them as Catholics. In the upper section there are no tonsures but copious beards, the style favored by the Protestant reformers.

To King Edward’s right Henry VIII lies on his death bed pointing towards his son and heir, lending legitimacy to the line of succession. Henry looks quite chipper for a man close to death, nothing like the reality of his bloated, diseased body at the end. His face is a copy of a late portrait by Holbein, preserving the image of Henry as handsome and heroic . The official to Edward’s left wearing the Order of the Garter is his uncle Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset and Lord Protector. To his left are other members of the Privy Council, notably the Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer in the white robe. It looks like his Protestant facial hair is just growing in; later portraits show a full flowing white beard. Other individuals who can be identified from their portraits are the Lord Privy Seal John Russell and William Paget. Somerset is clearly in charge here, but that is not what Henry intended. He meant for the Privy Council to rule jointly during his son’s minority. But, incredibly, Somerset, who was with the king when he died, managed to keep the death secret for three days while he consolidated power in his own hands. A zealous reformer, he was determined to accomplish the reformation of the English church that Henry had resisted.

Below the divide most of the figures are generic. In the center the Pope is being crushed beneath the Word of God. The worde of the Lord endureth for ever is a quotation from The Book of Common Prayer published in 1549 and revised in 1552. It established the approved prayers, rites, and ceremonies of the Church of England. On the ribbons flying from the Pope’s mitre his sins are named: idolatry, superstition, feyned holiness. And on the Pope’s chest a reminder of his mortality: all fleshe is grasse. The evil-looking monastic figures to the Pope’s right pull on chains attached to the king’s dais, representing the Catholic threat to the stability of the Protestant regime. The figures to the Pope’s left are opponents of reform. The cleric in the center with a tonsure is thought to be Cuthbert Tunstall, Bishop of Durham, an outspoken Catholic who even publicly burned an English translation of the Bible. The scene in the upper right shows men tearing down a religious statue in front of ruined buildings, perhaps a destroyed monastery. It is the only known contemporary depiction of iconoclastic destruction..

Aston’s most startling discovery is that the entire composition of the painting is copied from a drawing by the Dutch artist Maarten van Heemskerck. I can’t imagine how many hours she must have spent poring over drawings in old prayer books and Bibles until she came upon this source material. Heemskerck’s drawing of the biblical King Ahasuerus is dated 1563, and later Philip Galle made an engraving of it, resulting in a mirror image.

King Ahasuerus reclines in his bed just like Henry VIII and gestures in the same way, though without the pointing finger. The cushions and draperies around the bed are the same and it looks as though the anonymous artist used the table with its fringed covering for Edward’s dais. And if you wondered what a sphinx like woman with bare breasts is doing in a religious painting, well the strange bedpost was clearly copied from the foot of Ahasuerus’s bed, the bed coverings turned back in the same way. Though Henry’s bedpost is crudely painted compared to the original.

The inset picture of iconoclastic destruction is also copied from Heemskerck. He lived for a time in Italy and the classical ruins he saw there appear in many of his drawings. Here is his Destruction of the Tower of Babel alongside the scene in Edward VI and the Pope. The only changes are a statue atop the column instead of an urn and men prodding it down. Again the copy does not possess the fine detail of the original.

Edward VI and the Pope is like a late medieval version of a poorly executed cut and paste job. But it is the message that is important. Where does that message fit in the history of the English Reformation? It is easy in hindsight to think of the Reformation as inevitable, but it was not. It was more a case of fits and starts. Henry VIII never intended his break with Rome to lead to any doctrinal changes; for him it was purely a matter of his own personal interests. (Who does that remind you of?) If the pope had granted his divorce Henry would never have broken with Rome. Throughout his reign he resisted attempts to reform the English church along Protestant lines and remained a devout Catholic except for rejecting the Pope’s authority. One reason he soured on Anne Boleyn was because of her strident advocacy for reform. She had been influenced by reformist preachers she met during her youth on the continent and even owned religious books banned in England that were smuggled in by her friends. When Henry’s third wife, Edward’s mother Jane Seymour, once ventured an opinion, Henry is said to have reminded her that the last wife to bother him with opinions lost her head. Not surprisingly, Jane remained submissive.

But the Seymour family were ardent reformers. The young Edward was raised under their influence and taught by Protestant tutors. On Henry’s death the reformers, led by Protector Somerset, saw their chance. Protestant preachers who had been exiled on the continent came streaming home. A first priority was the destruction of religious imagery. Edward was encouraged to look to the Bible for models of kingship, particularly the kings who destroyed idols. The books of Kings and Chronicles recount how the young King Josiah turned away from the idols worshipped by his father:

and they brake down the altars of Baalim in his presence; and the images, that were on high above them, he cut down; and the groves, and the carved images, and the molten images, he brake in pieces, and made dust of them…

This woodcut comes from The Bishops’ Bible of 1568. It shows King Josiah seated on a dais with a scene of idol burning visible through a window above him to the left. Perhaps that was our unknown artist’s model for his inset scene of idol destruction.

Edward was hailed as the new Josiah of his age when in 1547 he instructed the clergy to –

“take away, utterly extinct and destroy” all shrines, pictures, paintings and monuments of superstition or idolatry in their churches, and to encourage parishioners to do the same in their own houses.

In 1548 he ordered the full removal of any remaining imagery and in 1549 the Act of Uniformity established The Book of Common Prayer . But these changes were not popular with everyone. In the same year a revolt known as the Prayer Book Rebellion broke out in Devon and Cornwall. Lancashire also remained loyal to “the old religion.” But for now Protestantism was the law of the land.

Everything changed when Edward died aged just fifteen. On his deathbed he named his cousin Lady Jane Grey as his successor in an attempt to keep England Protestant. But Henry’s eldest daughter, the Catholic Mary, popular and beloved by the people, had no difficulty seizing the throne. The unfortunate Lady Jane, still a teenager, was executed and the Catholic religion restored. All over England statues and crucifixes were pulled from their hiding places and put back on display in churches and homes. Many people had ignored the orders to destroy them. Mary’s harsh persecution of Protestants earned her the nickname Bloody Mary. About three hundred people were burned at the stake and at least another hundred died in prison over the five years of her reign. John Foxes’ Actes and Monuments, popularly known as The Book of Martyrs, detailed the suffering of Protestants under Mary and became a best seller. Archbishop Cranmer was among those who died in the flames.

The pendulum swung again when the Protestant Elizabeth succeeded her sister in 1558. She restored Royal Supremacy over the Church of England and The Book of Common Prayer. Antipathy to religious images was again at the forefront of reformers’ minds. They particularly abhorred roods, crucifixes, and statues of the Virgin and Child that had reappeared in the churches under Mary. Worship of the Virgin Mary was equated to pagan worship of the Goddess Diana. Denouncing the “puppets” that “stuffed” the churches of papists, Thomas Becon wrote:

I think, verily, that in the temples of the old pagans there was never found so much vanity and so many childish sights, as there be at this present day in those churches which are under the yoke and tyranny of that bloody bishop of Rome.

Early in Elizabeth’s reign decorative rood screens, crucifixes, and other artifacts were publicly burned in London. But there was a problem that would confound reformers and the Queen’s advisors for decades. Elizabeth herself, though a sincere Protestant, was not an ardent iconoclast. In 1559 gossip leaked out that she kept a crucifix and candles in her private chapel. The dispatches of Catholic ambassadors buzzed with the news. Philip II’s envoy the Bishop de Quadra wrote:

The fact is that the crucifixes and vestments that were burnt a month ago publicly are now set up again in the royal chapel, and as soon will be all over the kingdom…

Elizabeth’s clergy were described as being in a fever of anxiety. If she remained defiant should they resist, resign, or publicly berate her? There was a great deal of hand wringing. Thomas Sampson wrote to a mentor in Zurich:

Oh, my father, what can I hope for, when the ministry of Christ is banished from court, while the crucifix is allowed, with lights burning before it? And the wretched multitude are not only rejoicing at this, but will imitate it of their own accord.

Sometimes Elizabeth could be persuaded to remove the controversial objects, but they would soon reappear. There were several embarrassing episodes over the years. In 1562 someone broke the cross and candlesticks and reduced them to ashes. In 1567 they were attacked in the middle of a service. In 1570 Sir Francis Knollys incited the Queen’s Fool Patch to break the cross. By 1571 it was back in the chapel.

Elizabeth’s intransigence angered many reformers who believed she was setting a bad example for her people. For her part she declared she saw nothing in scripture that banned the cross. Clerics preached on the theme of idolatry citing Edward/Josiah as an example for her to follow. Ordinary people published broadsheets pleading with the Queen. In 1660 a group of ministers sent her a petition:

We most humbly beseech your Majesty… the establishing of images by your authority shall not only discredit our ministries … but also blemish the fame of your most godly brother, and such notable fathers as have given their lives for the testimony of God’s truth, who by public law removed all images.

It was to no avail. Elizabeth gave in on rood screens but purists were appalled at the idolatrous images in her chapel and many churches. Worst of all “that foul Idoll the Crosse on the altar of abomination.”

Some clerics went too far. On 25th February 1570 Edward Dering preached before the Queen, directly admonishing her and enumerating her failings. He prayed the Lord “would open the Queenes Maiesties eyes. Take heed, take heed.” Elizabeth was incensed and that was the end of Dering’s career.

In his ill-advised sermon Dering brought up another idolatrous object that was a focus of contention throughout Elizabeth’s reign: the Cheapside Cross.

The ornate column topped by a cross featured many religious statues including a Virgin and Child. This was a brazen idol looming over a major London thoroughfare. It was vandalized repeatedly by zealous iconoclasts. When the Virgin and Child statue was broken Elizabeth intervened to have it restored, and when the cross was removed because it was rotting, she again insisted it be restored. Reformers were outraged that the Queen had established a reputation as Protector of the Cross.

As she did on other issues, on religion Elizabeth I steered a careful middle way between the extremes in her fractious nation. Between Catholics and Puritans, between ordinary people, who clung to the cultural symbols of the old religion, and extreme iconoclasts. The strategy was useful in her diplomatic relations with the Catholic nations of Europe. In 1565 she told the Spanish ambassador Guzman de Silva: “Many people think we are Turks or Moors here, whereas we only differ from the Catholics in things of small importance.” Part of her mystique was keeping everyone off balance, not sure where her real sympathies lay.

In this context the painting Edward VI and the Pope is clearly a visual piece of the propaganda campaign that was directed at the Queen in an attempt to make her conform to iconoclastic purity. In sermons, broadsheets, prayers, and this painting, she was urged to be a Josiah like her brother. Perhaps the statue on the classical column in the inset scene, about to be knocked to the ground and destroyed, is the Virgin and Child on Cheapside Cross. But Elizabeth was no Josiah. Cheapside Cross remained in place until the Puritans controlled London and demolished it in 1643.

I liked your post. Besides being an interesting mystery story, it was a review of English history that included a few things that we have never heard about in the usual presentations and reviews…..Bill Ott

LikeLike