Perhaps it was the restlessness induced by quarantine that had me prowling my own bookshelves in search of diversion. I needed a break from the world of Thomas Cromwell in Hilary Mantel’s The Mirror and the Light. (I know it is tantamount to sacrilege to criticize Miss Mantel, whose Cromwell trilogy I agree is a magnificent achievement, but did we need the menu for his every meal in the year leading up to his execution, surely the last meal would have been sufficient?) In this grumpy mood I came upon The Singing Game by Iona and Peter Opie, the legendary English folklorists, a book I hadn’t picked up for many years. Divided into sections on over 150 games in 20 categories, it is a perfect choice to dip into for short diverting reads.

Perhaps it was the restlessness induced by quarantine that had me prowling my own bookshelves in search of diversion. I needed a break from the world of Thomas Cromwell in Hilary Mantel’s The Mirror and the Light. (I know it is tantamount to sacrilege to criticize Miss Mantel, whose Cromwell trilogy I agree is a magnificent achievement, but did we need the menu for his every meal in the year leading up to his execution, surely the last meal would have been sufficient?) In this grumpy mood I came upon The Singing Game by Iona and Peter Opie, the legendary English folklorists, a book I hadn’t picked up for many years. Divided into sections on over 150 games in 20 categories, it is a perfect choice to dip into for short diverting reads.

I first encountered the Opies in library school when I read The Classic Fairy Tales, a collection of well-known tales in the exact words of their first appearance in English, with historical introductions and commentary. Reviewing the book for my class I wrote: “these fairy tales are far more brutal, violent, and frightening than the versions I remember from my childhood.” It was a revelation. I went in search of their other books and found a prodigious body of research on folk tales, nursery rhymes, and the oral tradition of songs and games passed down by generations of children, the subject of The Singing Game.

Iona and Peter Opie stumbled upon their life’s work serendipitously. They met after Iona sent Peter a fan letter for his 1939 book I Want to be a Success. A correspondence and friendship followed and they married in 1943 when Iona was just 19. She gave up her dream of following in her father’s footsteps as a scientist, but her research skills would be put to good use nevertheless. The story goes that walking in a field one day Iona picked up a ladybird and recited the rhyme: “Ladybird, ladybird, fly away home, Your house is on fire and your children all gone.” Wondering about the origins of this rhyme they checked the local library but found nothing. Though they were not trained as academics they began the research that would last their entire lives, Iona carrying on alone after Peter’s death in 1982. They were certainly an eccentric couple, absorbed in their work to the exclusion of all else, even their own three children who they sent away to boarding school. In Iona’s 2017 obituary The Guardian noted:

The couple’s inquiries were exhaustive and exhausting. Peter did the writing; Iona, whom he called “old mother shuffle paper”, did the research. They worked three shifts daily in separate rooms, communicating by note in work hours – no social life, no money, picking nettles in the park to eat in lieu of greens.

They were pioneers in anthropology, doing fieldwork in over seventy schools for their 1959 study The Lore and Language of School Children and 1969’s Children’s Games in Street and Playground. Later Iona spent thirteen years observing playtime at a local school to record the “scatology and lewdness” left out of the earlier books. She certainly had no romantic notions of childhood, calling children “the greatest of savage tribes.”

The Singing Game meticulously charts the origins and history of both familiar and less known playground games, in English and American versions and in other cultures. Along the way the Opies debunk some myths. A case in point is that most common of games, Ring-a-Ring O’Roses:

Ring-a-ring o’roses,

A pocket full of posies,

A-tishoo! A-tishoo!

We all fall down.

I had always believed the story that this verse commemorated the plague. The ring o’roses was a red rash, the posies bunches of sweet-smelling herbs carried to ward off foul disease-carrying miasmas, the sneezes the first symptom, and then of course the victims fall down dead. The American version “Ashes, Ashes” likely comes from the word “ashem” or “ashum” used in Leeds and Sheffield for the sound of a sneeze.

Well the Opies pour cold water on this theory, pointing out that it didn’t originate until the mid 20th century, perhaps…

in satisfaction of the adult requirement that anything seemingly innocent should have a hidden meaning of exceptional unpleasantness, the game has been tainted by a legend that the song is a relic of the Great Plague of 1665…

The verse wasn’t written down until the nineteenth century. Some early versions use the word “curchey,” meaning curtsy, instead of a sneeze. In similar vein an early American version uses the word “stoop” and the last child to stoop down had to tell who she loved. European versions emphasize that the children skip around a bush, often a gooseberry or a rose bush, and squat or kneel at the end. The Opies conclude that the verse is likely a version of traditional May games, like maypole dances. The ring o’roses is thus not a dreadful mark of plague, but a pretty wreath of flowers worn on the head. I have to bow to their scholarly investigations, but I must say I found the plague story more compelling.

This is a great book to dip into at random to discover odd bits of history or something familiar from one’s own childhood. Here are witches’ dances and match-making songs, nonsense rhymes and country bumpkin humor. I remember playing the clapping game:

My mother said (clap)

That I never should (clap)

Play with the gypsies (clap)

In the wood (clap)

Because she said (clap)

That if I did (clap)

She’d smack my bottom (clap)

With a saucepan lid! (clap)

This game had an extra frisson of danger because every summer gypsies camped out in a field near my home. Sometimes the women came door-to-door selling clothes pegs. We would sneak through the woods to try to get a glimpse of the children, rumored to be barefoot and dirty. What freedom! But of course we couldn’t play with them.

My favorite singing game is Oranges and Lemons, a specifically London game with its London church bells. I love the tune and the way the names seem to toll off the tongue just like bells.

Oranges and Lemons, say the bells of St. Clemens,

I owe you five farthings, say the bells of St. Martins,

When will you pay me? say the bells of Old Bailey,

When I grow rich, say the bells of Shoreditch,

When will that be? say the bells of Stepney,

I do not know, say the great bells of Bow.

Here comes a candle to light you to bed,

Here comes a chopper to chop off your head,

Chip, chop, the last man’s head.

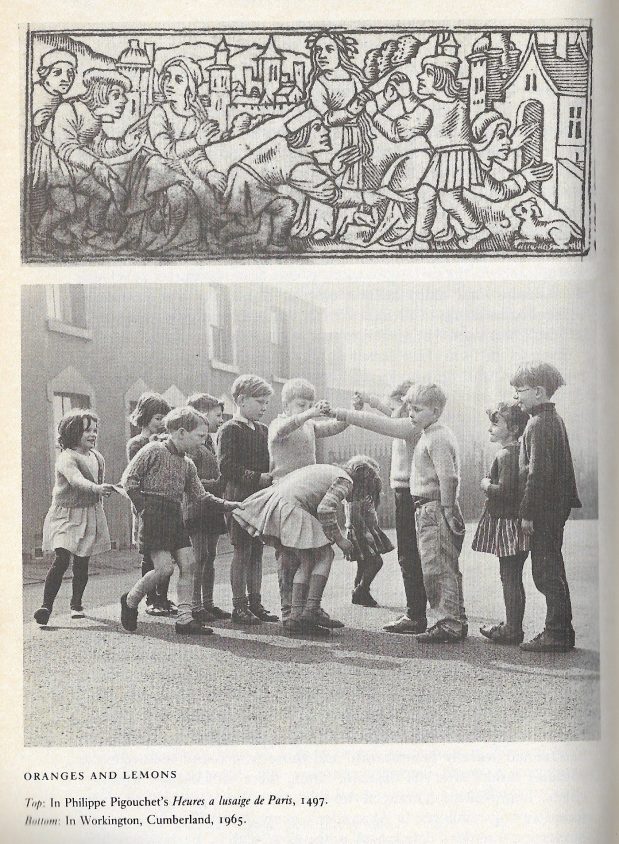

The game is played by two children forming an arch with their arms and the other children passing under in turn. When they reach the “chopper” line the arch children bring their arms down around the child passing under, who is now beheaded. “That chopping bit, it’s not really true because we only come down over their heads. They should be laying down so we could go Whack!” one seven year old concerned with authenticity confessed to the Opies. Their research reveals that the earliest text of the song from 1744 does not include the head chopping lines, while the earliest description of the game that does dates to 1853. That it is considerably older, or descends from an older game, is suggested by much evidence including the 1497 illustration that the Opies compare with a 1965 photo. But they find nothing to support a popular belief that it commemorates bells tolling the death knell as a criminal is led to his execution by torch-bearing guards.

Talk of beheadings brings me back to The Mirror and the Light. The pace quickens as Cromwell’s inevitable fate on the executioner’s block draws near. The feasts of eels with orange, capons with figs, Crustade Lombarde, jellied veal, onion tarts, spiced wine custard, saffron bread, and quince marmalade are over. Mantel brings her brilliant descriptive skills to Cromwell’s end. The reader sees and feels each dreadful moment up to the final agony of the axe.

A mine of information as always. I stand corrected on Ring o’Roses.

LikeLike

I LOVE this post!

LikeLike

I’m glad you like it! How did you hear about my blog?

LikeLike

I think you liked a post of mine at some point and so I looked at your blog; now, I follow you.

LikeLike

How lovely to hear from your again! I’ve missed your posts from the “former new world.” You always tell such interesting stories, and this one is perfectly delightful. At the beginning of the current pandemic, Hubby and I tried to recalled the nursery rhyme about the 1600s plague and the game all children — English and American and, probably, Canadian — played. I thought the rhyme/game had to do with mulberry bushes, but here you correct me with rose bushes. Now I remember. Keep safe and well!

LikeLike

Your subject matter always blows me away. Happy you have this outlet of writing and you have included me on your email list.Be safe. Anne

LikeLike

Your posts often lead me down a new-to-me rabbit hole, and this one is no exception – I’d never heard of the Opies, and I’m delighted to have a new avenue of information to explore. It’s an unusual surname… Is Peter any relation to Robert, who started the Museum of Brands, I wonder?

LikeLiked by 1 person