Does a concert of 16th and 17th century music have any relevance to our present moment?

The last thing I could have imagined as I sat in my high school classroom laboring over a test about the Rump Parliament was that decades in the future, in a far country, I would attend a concert featuring a ballad about the Rump Parliament. The Rump Parliament you ask? Well it’s one of those obscure English history topics like rotten boroughs or Lambert Simnel that you would be expected to know about for an exam. Hearing the popular ballads of the time would certainly have made it more interesting.

Long before newspapers, magazines, and media, street ballads were a form of political commentary and satire. The Folger Consort drew on these sources for their May concert Kings and Commonwealth, music of the English Civil War.

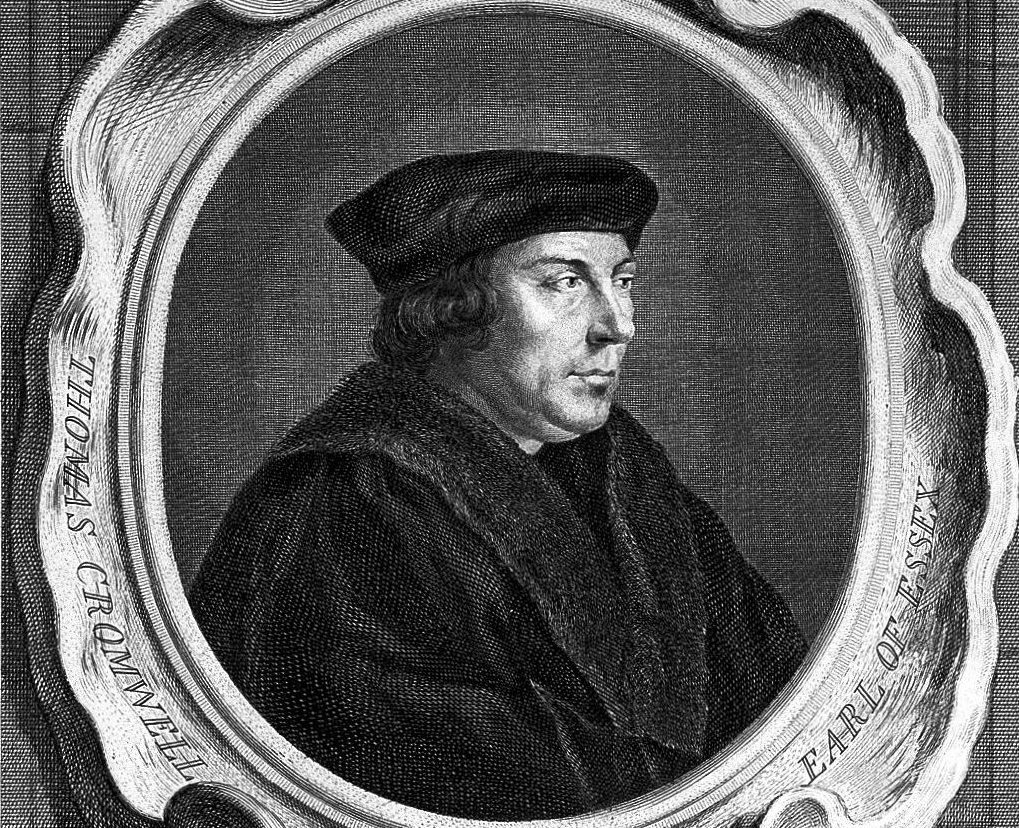

The program began with a Tudor Prelude, a reminder that it was the excesses of tyrannical kings that led to the Civil War. By chance I had just watched the final episode of Wolf Hall: The Mirror and the Light ending with Thomas Cromwell’s execution. Now I was treated to a broadside ballad celebrating his demise. Hilary Mantel created a sympathetic portrait of Cromwell in her novels. But at the time of his death Cromwell was a despised figure, hated for confiscating the wealth of the monasteries to enrich the king and himself, and for turning away from the Catholic faith. These themes come up in the ballad Trolle on Away, as well as distain for his humble origins.The meaning of the word trolle is obscure but may be related to a Middle English word for rolling or trundling an object, suggesting dragging Cromwell to his fate.

Here is a sampling of the verses. The meaning of “learne to spell” in this context is unclear, but ironic since the text reflects the idiosyncratic spelling of an age before standardization. But it works quite well phonetically.

Both man and chylde is glad to hear tell

Of that false traytoure Thomas Crumwell,

Now that he is set to learne to spell.Chorus:

Synge trolle on away, trolle on away,

Synge heave and howe rombelowe trolle on away.When fortune lokyd the in thy face,

Thou haddest fayre tyme, but thou lackydyst grace;

Thy cofers with golde thou fyllydst a pace.

Synge trolle on away…Both plate and chalys came to thy fyst,

Thou lockydst them vp where no man wyst,

Tyll in the king’s treasoure such things were myst.

Synge trolle on away…Thou dyd not remembre, false heretyke,

One God, one fayth, and one kynge catholyke,

For thou hast bene so long a scysmatyke.

Synge trolle on away…Thou myghtest have learned thy cloth to flocke

Upon thy gresy fullers stocke;

Wherfore lay downe thy heade vpon this blocke.

Synge trolle on away…

The concert mixed topical ballads with country dances and court music taking us from the Tudors to the Stuarts, James I and Charles I, whose stubborn belief in “the divine right of kings” would precipitate the Civil Wars.

And now we reach that fascinating topic, the Rump Parliament.

I may have been able to answer a test question about it back in my schooldays, but now I needed a refresher. So I plucked from my bookshelf The Restless Republic: Britain Without a Crown, a 2022 prize winning history by Anna Keay. Spoiler alert – it’s complicated!

The so-called Long Parliament had been in session since 1640 as the struggle between King Charles and Parliament erupted into war in 1642. By 1648 this Parliament favored a treaty with the King, but more radical forces, including the New Model Army, wanted to put the King on trial for treason. In December 1648 the Army took matters into their own hands in what became known as Pride’s Purge. Soldiers thronged the entry to the House of Commons while Colonel Thomas Pride stood at the door with a list of names. He refused entry to 121 members known as moderates in what historian Keay calls “one shocking, audacious and utterly unlawful act.” The members who remained were known as the Rump. They swiftly put an end to negotiations with the King and voted to try him for treason. On January 30 1649 King Charles I was executed.

The period that followed was chaotic as various factions jockeyed for power. Oliver Cromwell, head of the army, grew in influence and there was pressure on the Rump Parliament, now seen as too moderate, to dissolve itself so that a new parliament could settle the nation’s affairs. But the Rump dragged its feet and Cromwell (a very distant relative of Thomas) lost patience. On April 20 1653 he staged a military coup, entering the Commons chamber with armed soldiers and driving out the members with the words:

You have sat too long for any good you have been doing lately… Depart I say; and let us have done with you, in the name of God, go!

That was the end of the Rump. Oliver Cromwell, claiming God’s Providence as the source of his power, went on to rule as Lord Protector until his death in 1658. With the Restoration of Charles II in 1660 England was a monarchy once more.

The ballad featured in the Folger concert is called The Resurrection of the Rump set to the familiar tune of Greensleeves. It was very popular at the time and appeared in many collections of broadside ballads over the next century including Rump, or, An exact collection of the choicest poems and songs relating to the late times by the most eminent wits published in 1662. Apparently enough songs were written on this unlikely theme to fill whole volumes. Here are a few verses of The Resurrection of the Rump:

If none be offended with the scent,

though I foul my mouth, I’le be content

To sing of a Rump of a Parliament,

which nobody can deny.I have sometimes fed on a rump in sowse

and a man may imagine the rump of a louse,

But till now was ne’re heard of the Rump of a house,

which nobody can deny.There’s a rump of beef, and the rump of a goose,

And the rump whose neck was hanged in a noose;

But our’s is a Rump can play fast and loose,

which nobody can deny.When the parts of the body did all fall out,

some votes it is like did pass for the snout,

That the Rump should be king was never a doubt,

which nobody can deny.That the Rump may all their enemies quail,

they borrow the devil’s coat of mail,

And all to defend their estate in tail;

which nobody can deny.And whilst within the walls they lurk,

to satisfie us will be good work,

Who hath most religion, the Rump or the Turk,

which nobody can deny.Consider the world, the heaven’s the head on’t,

the earth is the middle, and we men are fed on’t,

But hell is the Rump, and no more be said on”t,

which nobody can deny.

You can listen to a performance of this song at the English Broadside Ballad Archive.

Neither the players nor the audience could ignore the contemporary echoes in this concert program. Indeed Robert Eisenstein, Artistic Director of the Folger Consort, addressed them directly in a word to the audience. He noted that this season’s theme Whose Democracy? was chosen well before November’s election but now looked prophetic. A country torn apart with deep divisions over politics and religion, power struggles between branches of government, a violent assault on a house of representatives, a would-be-king claiming absolute power ordained by God. Is our Congress any better than the Rump Parliament? Or will they be the subject of derisive songs and satires for decades to come? The title The Restless Republic is as fitting for our own times as for Britain in the seventeenth century.

The concert ended on a contemplative note, a reminder that all times are fleeting, with a poem by Robert Herrick (1591-1674) set to music by William Lawes (1602-1645).

Gather ye rosebuds while ye may,

Old time is still a flying;

And that same flow’r that smiles today,

Tomorrow will be dying.

I don’t remember anyone telling me about Lambert Simnel – thanks for the introduction!

As ever, Reet, you wear your erudition with such grace and ease!

LikeLike