On 30th December 1546 King Henry VIII lay dying, bloated beyond recognition and in excruciating pain from a festering wound on his leg, the result of a jousting accident years before. When his councillors brought him the final revision of his will he was too weak to hold a pen. So the document was signed using the dry stamp, a Tudor version of the autopen which has become so controversial recently. The dry stamp was a mechanism screwed onto paper to make an impression of the king’s signature, which was then inked over by one of his officials. Henry had authorized the use of this device in 1545 as his infirmities grew more severe.

Our current autopen issue is just another of the baseless scandals “trumped” up by President Trump and his acolytes to serve his interests. If autopen signatures on the pardons issued by President Biden can be declared invalid, then Trump is free to charge all his enemies with imaginary crimes. In fact many presidents as far back as Thomas Jefferson, including Trump himself, have used some type of autopen to sign official documents. Jefferson called his Polygraph Machine “the finest invention of the present age.” Richard Nixon, Lyndon Johnson, John F. Kennedy, and many other presidents routinely used an autopen. The question of its legality was definitively answered during the George W. Bush presidency in a 2005 memo from the Office of Legal Counsel. The challenge to Biden’s autopen signatures is unlikely to change history. But the case of Henry VIII’s will was of far more consequence for the history of the English monarchy.

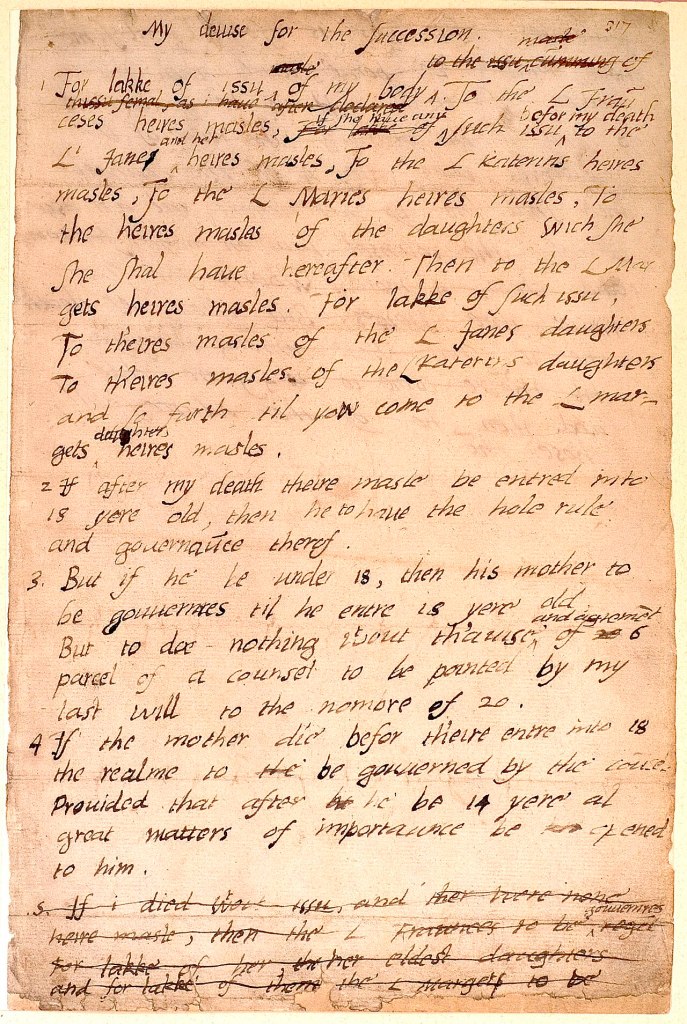

Henry’s complicated marital history and mercurial temperament had necessitated passing three different Succession Acts during his reign. The first two disinherited his daughters Mary and Elizabeth, declaring them illegitimate because his marriages to their mothers Catherine of Aragon and Ann Boleyn were invalidated, by divorce and treason respectively. The third Succession Act of 1543 named Edward, his longed for son by third wife Jane Seymour, as his heir. Mary and Elizabeth were declared legitimate after all and reinstated to the succession order if Edward died childless. If all three should die childless, an unlikely outcome that would actually come to pass, then the succession should follow Henry’s last will. The act included the fateful language that the succession order in his will would be valid if “signed with his most gracious hand.”

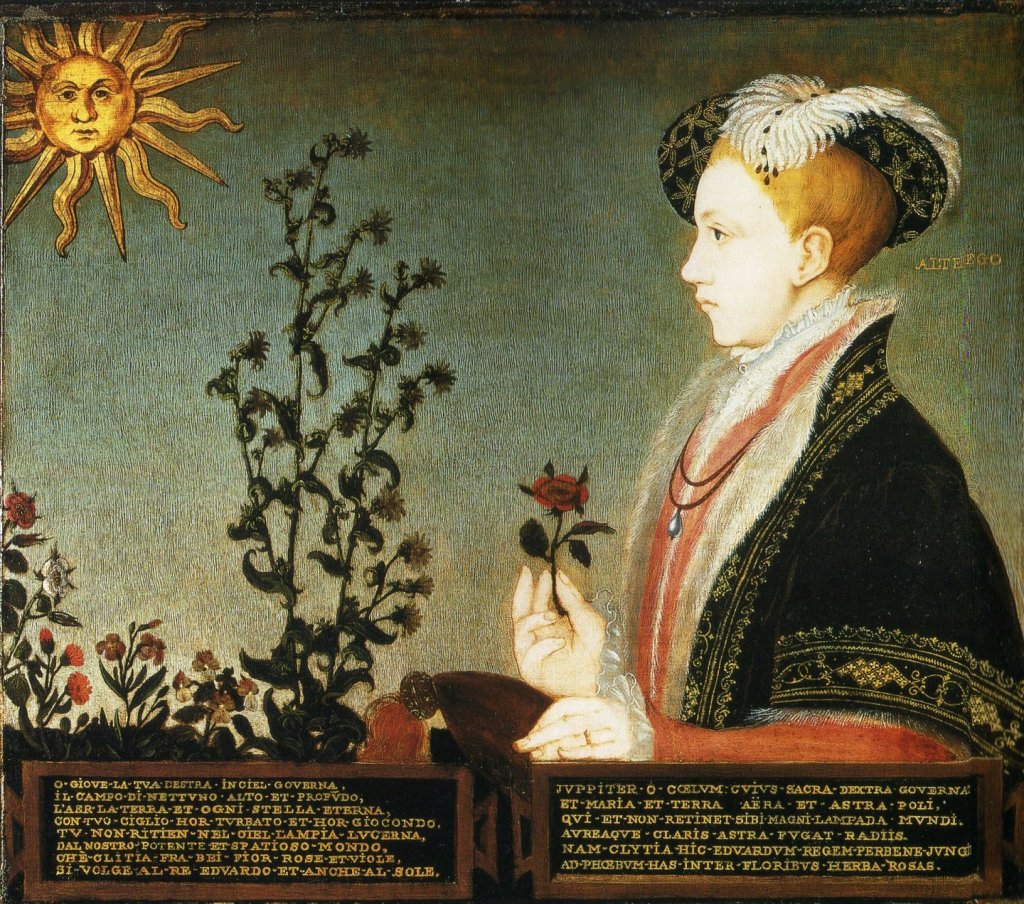

Portraits of Henry’s children Edward, Mary, and Elizabeth dated close to Henry’s death

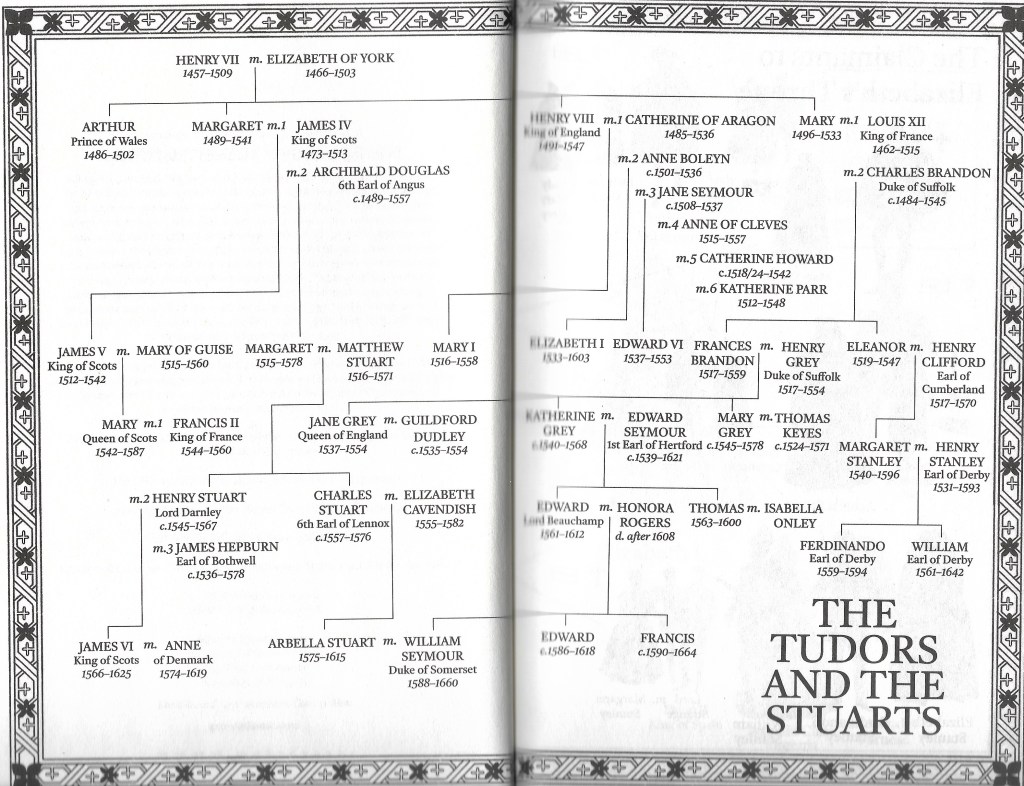

Henry’s last will stipulated that if all three of his children should die childless the succession would pass to the descendants of his sisters Margaret and Mary. But here is where it deviates from the expected order. Henry did not place the descendants of his elder sister Margaret next in line. She had married King James IV of Scotland so her heirs were the Scots Stuart family, including her granddaughter Mary Queen of Scots. Her daughter from her second marriage to Archibald Douglas had also married into the Stuart family producing more potential generations of Stuart claimants to the throne of England. Passing over this family Henry placed the descendants of his younger sister Mary next in line of succession after Elizabeth.

Following a brief childless marriage to King Louis XII of France, Mary had married Henry’s close friend Charles Brandon the Duke of Suffolk. Their elder daughter Frances married Henry Grey and had three daughters: Jane, Katherine, and Mary Grey. Younger daughter Eleanor married Henry Clifford Earl of Cumberland. Their grandsons Ferdinando and William Stanley were now also in the line of succession before the Stuarts.

Yes it’s complicated! Perhaps this will help.

Why did Henry favor the heirs of his younger sister? Well that family was as English as could be while the Stuarts were Scots, ancient bitter enemies of the English. Clearly Henry did not wish his throne to be taken over by the hated Scots even though they were blood relatives. But the manner in which his last will was signed was a fatal flaw in his carefully laid out plans for the succession.

…the seemingly insignificant detail of the dry stamp on Henry’s will opened the door, just a crack, that the dying king thought he had slammed shut on any future Scottish claimants to his throne.

Tracy Borman The Stolen Crown

Stuart claimants to the throne of England, descendants of Henry’s elder sister Margaret

Grey and Stanley claimants to the throne, descendants of Henry’s younger sister Mary

The teenage King Edward VI was the first to attempt circumventing his father’s will. A staunch Protestant who had championed many reforms to the English Church, he did not want his Catholic half-sister Mary to succeed him as Henry’s will dictated. He knew she would undo all his reforms and return England to the Catholic faith. Edward had always been sickly, suffering from numerous infections during his short life, including measles and smallpox. In 1553 when he was fifteen he suffered a last prolonged illness of the lungs, possibly tuberculosis. As he lay dying he signed a “devise for the succession” naming his Protestant cousin Jane Grey to succeed him. His last words were a prayer that England would be saved from “Papistry.” His prayer was not answered. Jane was proclaimed Queen, but the popular Mary summoned her supporters and marched on London. After nine days she prevailed and Jane Grey was executed for treason. Though Edward’s devise was written and signed by his own hand it did not carry the day.

Elizabeth’s succession, by contrast, was smooth. She was popular with the people and had attracted powerful supporters as it became increasingly clear that Mary would have no children. She learned an important lesson from her years as heir in waiting. A named heir attracted plotters who wished to usurp the throne for their own ends, whether of religion or ambition. After Wyatt’s Rebellion in 1554 Elizabeth was briefly imprisoned in the Tower, held in the same apartments as her mother Ann Boleyn. Mary’s councillors urged her to order Elizabeth’s execution but there was no evidence of her involvement in the plot. Instead Mary placed Elizabeth under house arrest at Hatfield where she remained until her half-sister’s death.

During her long reign Elizabeth famously refused to marry and refused to name her heir. (Tracy Borman’s new book The Stolen Crown presents new evidence to dispute the story that on her deathbed Elizabeth named James VI of Scotland her heir.) She operated a vast network of spies to counter any plots against her and took steps to neutralize her possible successors. She eventually, reluctantly, ordered the execution of Mary Queen of Scots, who during her long years of imprisonment in England was at the center of many Catholic conspiracies. She kept another Stuart claimant, the Lady Arbella, under close house arrest for so many years it drove the young woman mad.

Elizabeth’s English heirs fared no better. Katherine and Mary Grey each married in secret, infuriating the Queen. Katherine was imprisoned in the Tower for seven years. Her husband Edward Seymour was able to visit her and she gave birth to two sons in the Tower, another generation of potential English claimants. To counter this threat Elizabeth declared the boys illegitimate because their parents did not have her permission to marry. Both Katherine and her sister Mary died while under house arrest.

Loyalty was everything to Elizabeth so some other English claimants were able to avoid her wrath. The Stanley brothers Ferdinando and William did not actively pursue their claim and remained loyal. Ferdinando even foiled a Catholic plot. When he was asked to join the plotters he reported them to the authorities and served as a witness against them. Another Englishman with a strong claim to the throne was Henry Hastings Earl of Huntingdon who was descended from the Plantagenets. He professed disinterest in the throne and was rewarded with important positions in Elizabeth’s government.

When Mary Queen of Scots was executed the main Stuart claim to the throne passed to her son James VI of Scotland. He inherited the Scottish throne when he was only thirteen months old. His origins could not have been more melodramatic. Following the murder of his father Henry Stuart Lord Darnley, his mother Mary was deposed by the Scottish nobles who suspected her of involvement in the crime. She was imprisoned in Lochleven Castle but escaped to England. She never saw her son again. Instead of the help she expected from her cousin Elizabeth to reclaim her throne, she faced more years of imprisonment and eventual execution. James VI ruled through a council of Scottish nobles during his minority and was raised a Protestant. From an early age he believed his destiny was the English throne. James and Elizabeth wrote frequent letters to one another for more than thirty years. He sometimes begged her to name him her successor, while she offered advice on statecraft, keeping his hopes alive but never committing herself.

As Elizabeth’s procrastination over the succession extended into her old age, her councillors filled the void with their own calculations. They did not favor any of the women claimants, believing three queens in a row was inadvisable. Arbella Stuart was too mentally fragile to be considered. Katherine Grey was widely disliked, and Mary Grey was discounted for the most superficial of reasons, she was “little, crook-backed, and very ugly.” Among the male claimants Huntingdon was favored by many councillors, but more and more they looked north. Spies traveled back and forth on the road from London to Edinburgh bearing coded messages with intelligence on the Scottish King. James had his own spies reporting on the latest succession gossip in London and the health of the Queen. Religion was important; spies were tasked with discerning if James was a sincere Protestant or a secret Catholic. (There is a wonderful work of historical fiction on this theme: The King at the Edge of the World by Arthur Phillips.)

There was a major obstacle for James VI’s chances. The matter of Henry VIII’s will. As early as the 1560’s a Scottish diplomat asked Elizabeth for an examination of her father’s will to determine whether it was signed with the King’s “most gracious hand.” In the event that loophole was enough to deprive the English claimants of their trump card and restore the Stuarts’ right to inherit the English throne.

Was Henry VIII turning in his grave when James VI of Scotland was crowned James I of England? His opposition to the Scots was prescient. James was not a popular king. He preferred hunting, the company of beautiful young men, and focusing on his obsession with witches to affairs of State. He despised parliament and believed in the Divine Right of Kings, values he passed on to his son, the ill-fated Charles I. In two generations the Stuarts would lose the Crown that Henry had tried to keep from them.

But for the use of an autopen England may have been ruled by the English, not the Scots Stuarts or the German Hanoverians. English history would be a different story altogether.

One thought on “The Tudor Autopen”