Best Books of the Year lists are everywhere as the year winds down and book lovers start anticipating the new releases of 2026. Here is my list of favorites from 2025.

Poetry

Collected Poems by Wendy Cope

I had never heard of Wendy Cope until I read a review of this collection and learned that she is celebrated in England for her wit and accessible style. Lauded by the literary world and also a bestseller, she writes of the joys, heartbreaks, and mundane moments of ordinary life. One of her poems, The Orange, went viral on TikTok gaining her a new generation of fans. It affirms the value of small pleasures to keep us going in a complicated world. I particularly enjoyed her gentle satires of pompous literati and her parodies of famous poets. She resisted being named Poet Laureate, even writing an irreverent satire of the “state occasion” verse required. Here is a taste of her sly wit, the poem The South Bank Poetry Library, London in its entirety:

This is a pleasant library. I’d enjoy every minute

But for the danger of meeting other poets in it.

Fiction

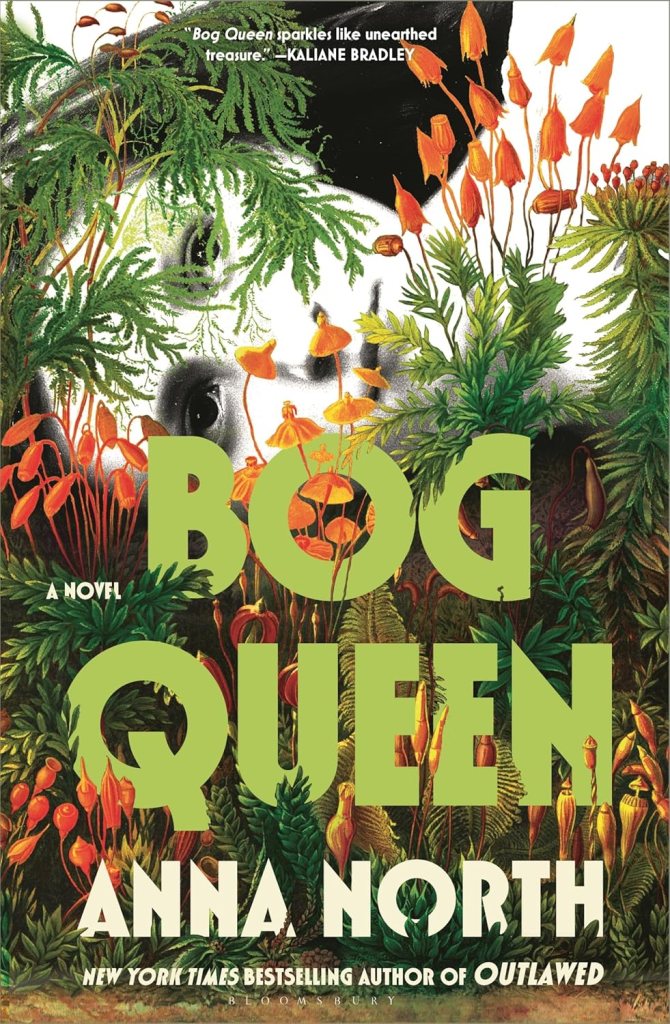

Bog Queen by Anna North

Seamus Heaney’s Bog Poems inspired the title of this tale of two women separated by two thousand years. Agnes is a forensic anthropologist called in to investigate a body found by peat diggers in a bog in northern England. At first the body is thought to be a missing local woman, but Agnes immediately recognizes that the wear pattern on the teeth indicates a much older origin. Perfectly preserved by the mossy bog environment, the woman is from the Iron Age, the early days of Roman Britain. In alternating chapters we follow the Druid priestess’s account of her journey to the Roman capital of Camulodunum and Agnes’s investigation into the cause of her death. A stab wound is ruled out because there are signs of healing. In the Druid’s narrative we learn of the violent encounter with a rival clan that caused the wound and how it was treated. Agnes’s work is complicated by a conflict with environmentalists who want to stop both the peat diggers and the archeological dig. The bog itself is a living character, speaking out at intervals to comment on human affairs and its sacred role in receiving the bodies of the dead. Enriched by the author’s research into Iron Age life and a lyrical writing style, this is a captivating read.

Continue reading “My Favorite Reading of 2025”