On My Bookshelf I discover the weird and wonderful history of English Place Names.

If you spend enough time in Great Sinns, Cornwall, you may find yourself on the road to Purgatory, Oxfordshire. Don’t take the fork to Pity Me, Durham, but seek forgiveness in Come-To-Good, another picturesque Cornish hamlet. Concocting imaginary itineraries like this is one of the pleasures of reading English Place Names by H. G. Stokes published in 1948. My copy shows its age, a bit tattered and worn. Stokes writes like a rather stuffy pedantic local history enthusiast, but his book is full of fascinating facts about the origin of English place names, many of them downright Rhude (Durham) like Mucking (Essex), Spital-in-the-Street (Lincolnshire), and Stank (Yorkshire).

English place names, according to Stokes, originated as simple colloquial descriptions, word pictures of a place. Before the age of maps or GPS people found their way from place to place by carrying the word pictures in their heads. By studying the original meanings of the words we can see a picture of what England looked like as much as 2,000 years ago. The words describe a rural landscape of woodland and heath, marsh and fen, hills and valleys, rivers and streams, dotted with dwellings and small settlements. Most of the oldest names are Celtic and Anglo-Saxon. Here are some of the most common name fragments and their meanings:

Ford is the most easily understood today. The word entered Old English from the Germanic furdu meaning a shallow place. Before Oxford was graced with “dreaming spires” it was just a place where oxen could wade across the river. Romford in Essex near where I grew up was originally named Rumford, nothing to do with drink but from the Anglo-Saxon rum meaning wide. Here the shallows of the Bourne Brook were remarkably wide.

Pen meaning hill gives us Pendleton (Lancashire) and Penrith (Cumbria). The suffix ton also refers to a high place. Combe or cym meaning valley is found in names like Ilfracombe and Combe Martin (Devon) while wen and den meaning dimple indicate a smaller valley.

Weald and wold meant woods or forest, telling us that the famous Sussex Weald and Cotswolds areas were originally forested. The Cotswolds don’t sound quite so cosy when you learn that it literally means woods owned by a fellow named Cod.

The suffixes snaed and ham originally meant a clearing in the forest while lea or ley meant a meadow by water. As most clearings and meadows would eventually have a dwelling or small settlement ham and lea came to mean village, along with stede, ton, burgh, and bury. Worth meaning enclosure also indicated a village, while stow was a meeting place, often a market, and wick was a farm.

These word pictures of features in the landscape were combined with the names of people who owned or lived there to form the place names we are familiar with. Thus Whipsnade, home of the famous zoo near London, means Willa’s clearing. Wirksworth (Derbyshire) was an enclosure owned by Weore, and Oswaldtwistle (Lancashire) was a piece of land between the forks of a river owned by Oswald. The major city of Birmingham started out as Beorma’s ham.

Sometimes the word pictures can be all too graphic. The unfortunately named Shitterton (Dorset) literally means “farmstead on the stream used as an open sewer.” Modern residents funded a heavy stone sign as the wooden ones were so frequently stolen by tourists! Among other unpleasant sounding place names are Blubberhouses (Yorkshire), Catsbrains (Buckinghamshire), Drinkers End (Worcestershire), Muggins (Essex), Ugley (Essex), Woeful Dane Bottom (Gloucestershire), and Wretchwick (Oxfordshire). The original meaning of some of these names, though, is quite different from how they sound today. The word catsbrains referred to a type of soil, a mixture of clay and chalk, while blubber meant bubbling, so the name is actually “houses by a bubbling brook,” rather a nice location.

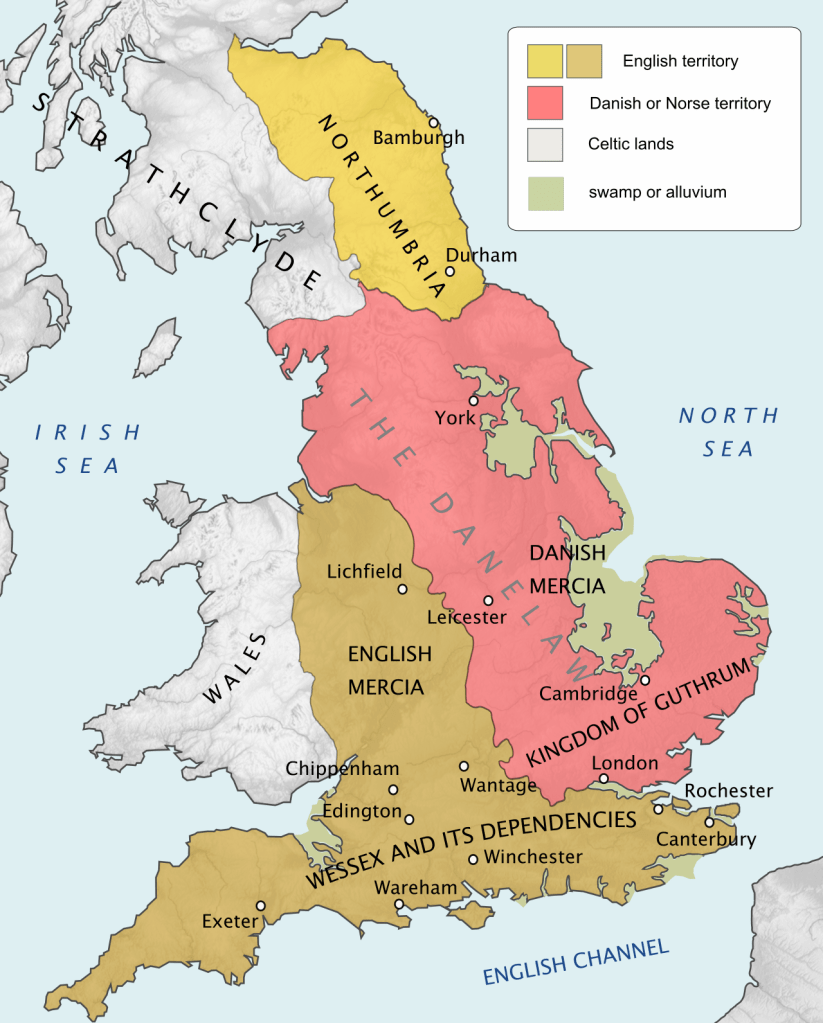

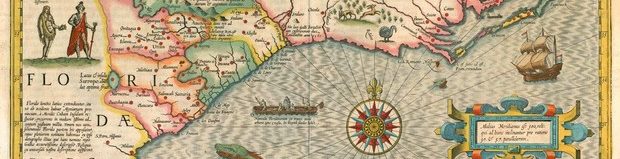

The distribution of English place names record the waves of immigrants who settled different parts of the island over the centuries. The oldest names are Celtic and reflect how the Celts were driven westward to Wales and Cornwall by the Anglo-Saxon and Viking invasions. The Romans left their mark, notably with London from Londinium, though that name possibly derived from a Celtic word meaning wide river. Castra and chester in place names indicate where the Romans built their forts. They were often the beginnings of large towns like Manchester and Leicester. The Anglo-Saxons favored staking ownership with their own names, but also often the animals they raised. Swinton (Lancashire) is literally pigs’ village. Following the conversion to Christianity names referring to churches and steeples became common, while the suffix minster meant a religious community. Next came the wave of invasions from Scandinavia. The Danes controlled East Anglia and Yorkshire and here you can find names with the suffixes toft, thorpe and by like Lowestoft (Suffolk) meaning Hlothver’s homestead. In Cumbria in the north-west Norwegians predominated and here are names ending in garth and wick meaning a dairy farm. The Norman invasion of 1066 brought a wave of French names, many recorded in the Domesday Book alongside the old Anglo-Saxon name. Often the new landowners added their name to the old one, as in Ashby-de-la-Zouche (Leicestershire) formerly Ashby, meaning the homestead near the ash tree, now owned by the Norman Zouche family.

Have you ever wondered if any of those villages in English murder mysteries are real? Some have very appropriate names like Great Slaughter where the Sister Boniface books and TV show are set. The fictional village is based on Lower Slaughter and Upper Slaughter ((Gloucestershire). Stokes points out rather testily that amateur historians claim the name refers to a bloody battle on the site, but in fact the original word was slough meaning a swamp. Midsomer is the fictional county with the highest body count, considering the long-running Midsomer Murders series. The county got its name from the village of Midsomer Norton (Somerset). Writer Anthony Horowitz picked it by searching a map of Somerset for a quintessentially English name. The original meaning is “midsummer festival of St. John,” highly appropriate as so many episodes begin with a village festival of some kind!

Now I’m going to take an imaginary journey through the Essex towns I knew in my youth, but like a traveller long ago I will take no map, just follow the word pictures I have learned in this book.

I begin just north of the muddy river (Thames) at Daecca’s homestead (Dagenham) where I was born and follow the path across the heath (Heathway).

I head towards the place where the Berecingum dwell among the birch trees (Barking) and then walk uphill towards the hall owned by the monks of Waltham Abbey (Upminster).

Now I must find the wide shallow part of the Bourne Brook (Rumford) so I can cross over and take the track to the heath where I can bathe my tired eyes in the waters of St. Chad’s Well (Chadwell Heath). St. Chad was an Irish monk who became Bishop of Mercia in 699. The holy waters of this spring are said to cure ailments of the eye. I spent most of my childhood in this suburban town where a small plaque marks the site of the spring, once a place of pilgrimage.

From here I head to the dwelling place of the Haeferingas near the royal hunting lodge (Havering-atte-Bower), a place once owned by William the Conquerer.

Then a nostalgic trek to the town where I went to school from the age of eleven to eighteen. I turn north at Gallows Corner (no explanation needed for this name) and look for the clearing in the woods made by a forest fire (Brentwood).

Finally I need a quiet place to stop and rest, a place where we had Sunday picnics in my youth. I make my way to the high woods owned by the monks (Hainault Forest).

All the weird and wonderful names whirl in a jumble through my head – Christmas Pie, Cockstroop, Devil’s Beeftub, Giggleswick, Muggins, Piddle Trenthide, Puddinghole, Saffron Walden, Snoring, Weeks-in-the-Moor, Wig Wig. Occasionally they arrange themselves like Scrabble tiles and a pattern emerges, inspiring this:

From Bachelor’s Bump to Cupid’s Green

He sought his Heart’s Delight,

But when he stopped in Grope Lane

Angel put up quite a fight.Ride on to Impudent Garden

Yours Truly

You Shambelly, she said,

For when I meet a Studley man

In Vowchurch we shall wed.

Another nice one, Reet. It brought to mind my brotherPeter’s favourite book ‘The Meaning of Liff’ by Douglas Adams & John Loyd, a very different and hilarious account of place name meanings which should grace every restroom. For them Lowestoft means either the balls of wool which collect on nice new sweaters, or the correct name for navel fluff. And Oswaldtwistle (allegedly from the Old Norse) refers to a small brass wind instrument used to summon Vikings in to lunch when they off playing in their longships.

It also reminded me of my old friend the late Madge Derby, co-founder of The History of Wapping Trust, who wrote ‘Waeppa’s Place: a history of Wapping’. What has always puzzled me is that while this refers to the East London hamlet where both your dad and I worked, how does it reate to Wapping in Bristol, now also a haven for rich trendies.

LikeLike

I was in Yubberton only last week. It’s the Gloucestershire name for the village of Ebrington. The pub there, the Ebrington Arms, brewed beer there until 5 years ago. My favourite was called Yubby, now sadly unavailable. I settled for Moreton Mild, from the North Cotswold Brewery 3 miles away.

LikeLike