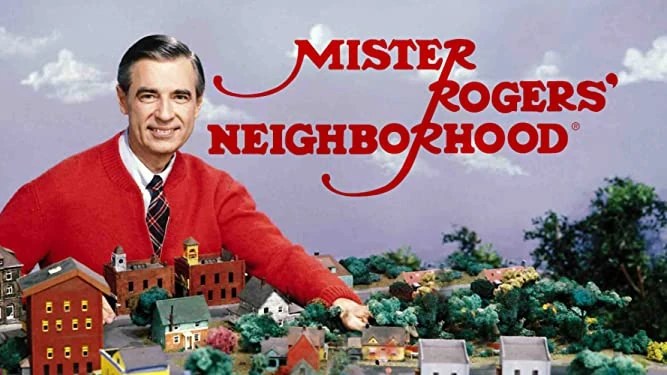

I used to love watching Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood when my children were small. So calm, so soothing, so… well, neighborly. Sometimes I even watched when the children weren’t around. A restful oasis in a stressful day. In Mr. Rogers’ world all the neighbors were nice and friendly and helpful. Ever ready with a kind word or a helping hand. None of them yelled “get off my lawn!” If only it were so.

Today Mr. Rogers is a sweet memory. If you spend any time on the Nextdoor app, which purports to bring neighbors together, you will find yourself in a dark dystopian world where every teenager in a hoodie is a potential carjacker, every delivery man a potential home invader, and every dog walker intent on spreading dog poop over your lawn. Fear and loathing stalk the posts on Nextdoor, the comment threads a cesspool of complaints, anger, stereotypes, and often outright racism. An occasional lone voice bleats for civility.

The fiendish alliance of Nextdoor and Ring Doorbell amplifies the fear factor. The dark, grainy videos make even the most upstanding citizen look suspicious. “Do you recognize this man? This woman? These kids?” Neighbors possibly just going about their lives caught by Ring’s ever watchful eye, and condemned as criminals by their neighbors. Fear and suspicion stoked to lethal levels. The consequences can be fatal – a young man shot for going to the wrong door and a young woman shot for going up the wrong driveway are recent headlines.

Technology has amplified it, but this is not really anything new. Before there was Ring there was the twitching of net curtains at the window and the prying eyes of would-be Miss Marples. Before social media word of mouth gossip networks spread rumors and falsehoods over the garden fence and into gathering places like the local Post Office, the village green, markets, cafes, pubs, and even church services. Feuding neighbors and accusatory finger pointing are a constant feature of social history through the ages.

The history of witch trials in Europe and America are replete with tales of neighbor accusing neighbor. In one notorious case in Essex in 1645 Elizabeth Clarke of Manningtree, an elderly widow, was accused by her neighbors of causing the death of two cows and a baby. All had fallen ill after passing by her home; ridiculously that was enough evidence to arrest her. She was executed in Chelmsford along with fourteen other supposed witches, so frail that she had to be lifted into the noose. Cheering crowds celebrated the deaths. In America the notorious Salem witch trials were fueled by the same hysteria with accusations by neighbor upon neighbor. The trials only came to an end in 1693 when Governor William Phips’ own wife was accused. This brought him to his senses, but not before 25 innocent men, woman, and children were put to death. The same people who point fingers at their neighbors on Nextdoor today would no doubt have accused them of witchcraft had they lived back then.

I recently read a novel about the toxic results of neighborhood gossip set in an English village long before the digital age. Leadon Hill by Richmal Crompton is a sharp little dagger of a book. I was surprised to come upon it as I didn’t know that the author of the popular children’s series Just William also wrote for adults. I loved those light hearted stories about the exploits of the always in trouble rapscallion William. But Richmal Crompton’s imagination had a dark side. The village of Leadon Hill is ruled by Miss Mitcham, a vicious curtain twitcher who does not take kindly to outsiders. When the beautiful, cosmopolitan Helen West moves into the village Miss Mitcham is determined to sabotage the young woman’s efforts to fit in and make friends. Gossip and innuendo slowly erode any hope of a happy ending and expose a far from cosy image of village life.

What started me thinking about the malign influence of Nextdoor was coming across a review of Wicked Little Letters, a new film starring Olivia Colman. If that seems a bit random, well the film is based on a true story told by social historian Emily Cockayne in her academic study Cheek by Jowl: A History of Neighbours. The book traces neighbor relations and disputes from the early middle ages to the present. It seems people have been complaining about their neighbors’ dogs for over 700 years. Privies were also a regular source of conflict. In 1333 the de Aubreys complained that their neighbors had removed a board from the privy so their “extremities” were exposed when they used it. In Samuel Pepys’ famous diary he complains that the privy next door is leaking into his parlour.

During her research in local newspapers from the 1910’s and 1920’s Cockayne came across a case of poison pen letters in the Sussex seaside village of Littlehampton. In 1919 Edith Swan accused her neighbor Rose Gooding of writing “wicked little letters” to her and other villagers. Gooding was put on trial for libel; the letters deemed “indescribably filthy” and some too offensive for the jury to hear. I’ll refrain from quoting them but if you’re curious this Guardian article has plenty of examples. Although Swan and Gooding were both working class, Swan thought of herself as “respectable” while Gooding was “rough and foul-mouthed” and the mother of several illegitimate children. In the eyes of the police, Cockayne says, Gooding “looks the part and acts the part… an obvious suspect.” But was Swan entirely innocent? The review withholds the answer as a teaser for the film.

If you can’t wait for the answer check out Cockayne’s next book, Penning Poison: A History of Anonymous Letters, where she expands on the Littlehampton story. The book surveys English letters from 1760 to 1939 exposing all kinds of scandal, class prejudice, and tragedy. The chapters are arranged by type of letter from gossip to threats, obscenity to libel. From “Major Eliot’s maiden sisters” to “Lord Dorington’s in danger” and “er at number 14 is dirty.” I can’t help wanting to know the stories behind those tantalizing chapter headings so perhaps my appetite for historic nastiness is greater than for today’s version.

Those letter writers are no different from the internet trolls of today. They used the mode of communication most readily available to them at the time. Poison pen letters spread suspicion, paranoia, and anxiety throughout communities just as so many Nextdoor and other social media posts do today.

Perhaps we’d all be more neighborly if we stayed off Nextdoor and watched reruns of Mr. Rogers instead. And for the record, my own neighbors seem like lovely people. At least I haven’t seen any of them starring in a sinister Ring Doorbell video yet.