FICTION

Caledonian Road by Andrew O’Hagan.

How could I resist a book billed as the Dickens of contemporary London? It did not disappoint. The city itself is a main character and according to the Guardian “The London that emerges from its 600-odd pages resembles a vast, rotting carcass picked over by carrion.” That doesn’t sound very appealing, but the book is constantly entertaining and mordantly witty. The central character is middle aged writer and academic Campbell Flynn who rose from humble beginnings to celebrity, but whose life is now spiraling out of control. Around him swirls a cast of characters high and low, from aristocrats to human traffickers, working class students to Russian oligarchs. We can’t help but root for the hapless Campbell as he is snared in a plot of corruption and scandal he can’t escape. The usual suspects of the English class system and hypocritical politicians get a merciless drubbing.

Creation Lake by Rachel Kushner.

Like Birnam Wood, on my favorites list last year, Creation Lake is about a radical environmental group, this time in rural France near a cave where Neanderthal remains were discovered. But unlike the gardening collective of that novel, Le Moulin plans violence. An American spy-for-hire, a woman using the undercover name Sadie, infiltrates the group. Kushner successfully combines the suspenseful plot of a thriller with a serious novel of ideas. Sadie becomes fascinated with letters from Bruno, a legendary activist who inspired the founders of Le Moulin. He believes that Neanderthals had a superior way of life, in harmony with nature, and that Homo Sapiens has gone tragically astray. Is Sadie’s mission to disrupt Le Moulin’s violent plans or to entrap them by urging them on? Where do her true loyalties lie? This novel was deservedly short-listed for the Booker Prize.

Enlightenment by Sarah Perry.

Like her break-out novel The Essex Serpent Perry’s latest is set where she grew up, a strict Baptist Church community in estuary Essex, a land of mud flats and brooding grey skies. It is the story of two misfits, of unrequited love, of astronomy and faith. Thomas Hart is a middle-aged closeted gay man who writes a column for the local newspaper. He has a protective relationship to young Grace Macauley, the free spirited motherless daughter of the pastor. It is 1997 when the Hale-Bopp comet is expected to set the night sky ablaze. As they await the comet Thomas and Grace become obsessed with the story of Maria Valduva, an amateur astronomer who once lived in the local mansion, now a museum. Her ghost is said to haunt the grounds. From these elements Perry spins a magical tale told in gorgeous prose, full of wonder at the heavens and compassion for human souls.

North Woods by Daniel Mason.

I’ve loved all Mason’s books since his first, The Piano Tuner, for his ability to immerse us completely in distant worlds. Here he follows the history of a small plot of land in the woods of Western Massachusetts. The clearing is first settled in the 1600’s by a young couple escaping their oppressive Puritan community. Years later a mother and child kidnapped by native people seek refuge there; violence erupts; a tree grows from an apple seed in a dead soldier’s stomach; a veteran of the Revolutionary War starts an apple orchard business inherited by his reclusive twin daughters; an escaped slave from Maryland finds safety there; a landscape artist buys the property for his family, while carrying on a clandestine affair with a famous writer. Later owners find the house haunted by the ghosts of the former residents, including a murder victim buried under the floorboards. This is not only a dramatic story of human lives but also of the land itself, how the environment changed over the centuries. Mason writes beautiful descriptions of nature and as the story reaches the present he surprises us with an unexpected twist.

You Are Here by David Nicholls.

Another book I could not resist because of the setting, the English Lake District. I spent two hiking holidays there, once as a teenager and once when my children were teenagers. In a memorable moment as she slipped on sheep droppings on the steep fells my daughter uttered the immortal line “Only crazy English people would think it is fun to hike in the rain!” Well some of the characters in this book would sympathize. Five people set off on the coast to coast walk from the Lake District through the Yorkshire Dales and Moors to the North Sea. Cleo brings her teenage son and has invited three friends who don’t know one another. Conrad, a ridiculously handsome pharmacist, Michael, a middle-aged geography teacher whose wife has recently left him, and Marnie, a divorced Londoner reconciled to being alone. After three days Michael and Marnie are the only two continuing on. Not that Marnie is enjoying it. Disappointed that Conrad has dropped out, bored by Michael’s teacherly lectures on the landscape, exhausted by the grueling climbs, and underwhelmed by the famous vistas, often obscured by mist. As they trudge on a tentative romantic relationship develops despite their differences. This is a touching and very funny story of two bruised people finding love in the most unexpected circumstances.

NONFICTION

Cloistered: My Years as a Nun by Catherine Coldstream.

As a former convent schoolgirl whose two best friends became nuns, I’m always drawn to memoirs that reveal what really goes on behind the cloister walls. Catherine Coldstream was not born a Catholic but converted in her 20’s after her father’s death plunged her into a psychological crisis. It is said that converts often take things to extremes and that is certainly true of Catherine. She joined the Carmelites, a strict enclosed order, in a remote convent in Northumberland. We know from the beginning that all did not go well. In the first scene she is escaping, running across the fields in the middle of the night after ten years of harsh convent life. It is not the extreme asceticism that upsets her. She embraced the silence, the rough clothing, the constant hunger from spare rations, the bare cell.. It was the emotional coldness and even cruelty of her fellow nuns that wore her down. It turns out nuns are just flawed human beings like the rest of us, far from saints. And the claustrophobic convent life brings out the worst: meanness, petty jealousy, rivalries, and even power politics. Catherine has nowhere to go on that desperate night and returns to the convent. When she does leave she has a difficult time adjusting – all the noise! – but creates a new life for herself. Her memoir is a beautifully written and psychologically astute study of survival.

The Garden Against Time: In Search of a Common Paradise by Olivia Laing.

This is my favorite kind of nonfiction book. Ostensibly about one subject, a garden, it meanders down side paths into many other related subjects, literature, history, and more. Newly married, Laing has her own garden for the first time in her life. Created by Suffolk landscape designer Mark Rumary, the garden is now an overgrown wilderness. Through the course of the book and the seasons Laing clears the weeds, identifies plants, and replants, to restore the garden to its former glory. The work is grueling but she persists, having nothing else to do during the isolation of COVID. Along the way she discusses the concept of paradise as a garden in Milton’s Paradise Lost, poet John Clare’s nature writing, novelist Rose Macauley’s description of wild gardens springing forth spontaneously in London’s bomb sites after World War II. Famous gardeners of the past make an appearance, notably Capability Brown and Gertrude Jekyll. Laing also examines the darker social history of gardens. The fabled gardens of the English aristocracy in the 18th century were financed by West Indian sugar plantations and the slave trade. Much of the land that became famous gardens was seized in the 18th and 19th century Enclosure Movement. Landowners fenced off land that had been held in common for grazing and growing food, causing hardship and social unrest. But Laing always returns to the deep pleasures of gardening in the present, a balm for mind and body.

God’s Ghostwriters: Enslaved Christians and the Making of the Bible by Candida Moss.

This is a truly eye-opening book that completely overturns our assumptions about how the Gospels were written. Moss is a Professor of Theology in the UK whose research here focuses on how writing was done in the Ancient World. If we imagine that the classic Greek and Roman authors actually did the physical work of writing Moss shows how wrong we are. No, they dictated to their slaves. Writing was hard physical labor. Slaves were trained in the art from childhood. They sat cross-legged for hours, tablets balanced on their knees at an awkward angle, which often left them crippled in later life. So it was with the early Christians who first wrote down the Gospels. Christian slaves wrote the words attributed to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, perhaps dictated by these named individuals or by others who had heard their stories. Pauls’s letters too were dictated. Sometimes the writer is hiding in plain sight. Moss points to the Letter to the Romans which includes the line “I, Tertius, the writer of this letter, greet you in the Lord.” Moss shows how the work of writing was a collaboration between the speaker and the writer, the choice and emphasis of words subtly changing the text. Enslaved people were thus in a crucial position to refine and influence the concepts of Early Christianity. This book is indeed a revelation.

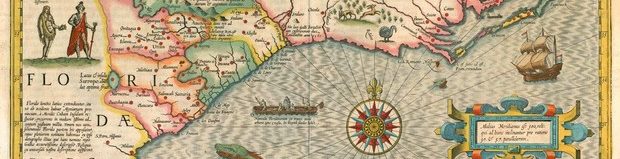

The Wide Wide Sea: Imperial Ambition, First Contact and the Fateful Final Voyage of Captain James Cook by Hampton Sides.

Captain Cook’s reputation has veered from hero explorer to imperialist villain in recent years. Hampton Sides charts a course between these extremes to give us a balanced account of a complicated man in this page-turning account of Cook’s last voyage. Cook saw his mission as charting accurate maps of the Pacific; he was less enthusiastic about the imperial “plant the flag” part of his duties. And, unlike many of his contemporaries, he respected the people with whom he made first contact and was curious about their beliefs and customs. He even had the insight that contact with Europeans was harmful to their societies. But on this last voyage Cook seemed a changed man to his crew, quick to anger and impose severe punishments. Sides examines how this contributed to the fateful cultural misunderstandings that led to his murder in Hawaii. By a remarkable coincidence Cook’s ship approached the island in the exact way that Hawaiians expected a god would return to them. At first they treated him as a god, but all too human interactions disillusioned and angered them, leading to the tragedy. Within the story of Cook is the story of another man, equally compelling. Aboard ship was a young Tahitian prince, Mai, returning home after a visit to London. He had gone there willingly to seek British support in his war with a rival. Mai was treated as an honored guest by high society who marveled at his natural good manners. He too was a changed man on this voyage.

Young Elizabeth: Elizabeth I and Her Perilous Path to the Crown by Nicola Tallis.

Does the world need yet another book about Elizabeth I? When I read my first biography of the queen for a school project I thought it so complete that there would be no need for another one! Since then scores of books have rolled off the presses examining every aspect of Elizabeth’s life, particularly those neglected by the male historians of the past. Among my favorites are Elizabeth’s Women: The Hidden Story of the Virgin Queen by Tracy Borman and The Queen’s Bed: An Intimate History of Elizabeth’s Court by Anna Whitelock, both revealing the real woman behind the myth. Nicola Tallis fills a gap by focusing on Elizabeth’s youth, often glossed over lightly in full biographies. She reminds us that there was nothing inevitable about Elizabeth’s rise to the throne, and she did not grow up with such an expectation. She shows us a young Elizabeth all too aware of her precarious position. If either her brother Edward or her sister Mary had lived to produce an heir she would have been as forgotten by history as Arabella Stuart, another young woman who might have inherited the Crown. Arabella’s life ended as a prisoner in the Tower. Elizabeth’s might have too. She was imprisoned for a time by her sister Mary, held in the same apartments as her mother Anne Boleyn before her execution. This must have been a terrifying experience, just one in a series of upheavals and reversals of fortune that forged her strong character.

Please add your own favorite books of 2024 in the Comments below. Wishing you all a Happy New Year of reading in 2025!

Fascinating bibliography as ever, Reet. Reflecting on my reading over the last year I notice an ‘unconscious bias’ towards the factual and the Irish, although I also learned a lot from Michael Levine’s ‘Zionism and History’ and Gharda Karmi’s ‘One State’, both helpful to understanding of the plight of Palestinians and Jews. My big read was ‘Decades of Deceit: The Stalker Affair and its Legacy’ a painstaking re-evaluation of police/political, corruption by an old friend Paddy Hillyard,who used to chair the National Council for Civil Liberties. `Equally enthralling was Eoghan MacCormac’s ‘Captive Columns: 1865-2000’ about republican prison publications.

I enjoyed two autobiographical accounts, the atmospheric ‘Reading in the Dark’ by Seamus Deane, and ‘Resting Places: On Wounds, War and the Irish Revolution’ by Ellen McWilliams. You would enjoy the latter, Rita, because it unfurls through the books and people in her life as she comes to terms with some startling revelations (not of the child abuse variety) about her family. She spoke about the trauma of tracing her family history at an event in Bristol.

I was least impressed with ‘Old God’s Time’ by Sebastian Barry, a writer whose earlier work has always impressed me, but I did get the message of Paul Lynch’s award winning ‘Prophet Song’ a useful parable for our times.

My son Sean introduced me to short story writer Kevin Barry. and the extraordinary talents of Limerick’s Blindboy. This year it was ‘Blindboy BoatClub: Topographia Hibernica’. I not really into podcasts and rarely listen to them but the Blindboy podcast is worth a visit; it is strong meat but also funny and enchanting. Scroll through the whole lot and see what title takes your fancy.https://shows.acast.com/blindboy

Sean is involved (music and impromptu words) in the weird and wonderful Limbo Calling podcast, try it out with this one: https://limbotapes.podbean.com/e/1-fear-swim/

Two other books from the year, Naomi Klein’s wondrous ‘Doppelganbger: A Trip into the Mirror World’ anther parable for our times; and Leon Surmelian;’s “I Ask You Ladies and Gentlemen’ – a child’s poignant account of the Armenian genocide.

I am still plodding through ‘Stephen & Matilda: The Civil War of 1139-1153′ by Jim Bradbury. Having helped a couple of academics during the year looking into the history of Stephen & Matilda Tenants’ Co-op, which I helped to set up 50 years ago, I thought it might be useful to find out more about our name sakes. (There were two Matildas at the time, which made it all extra confusing; and I never knew there had been two Civil Wars in England.)

Happy new reading year in 2025!

LikeLike