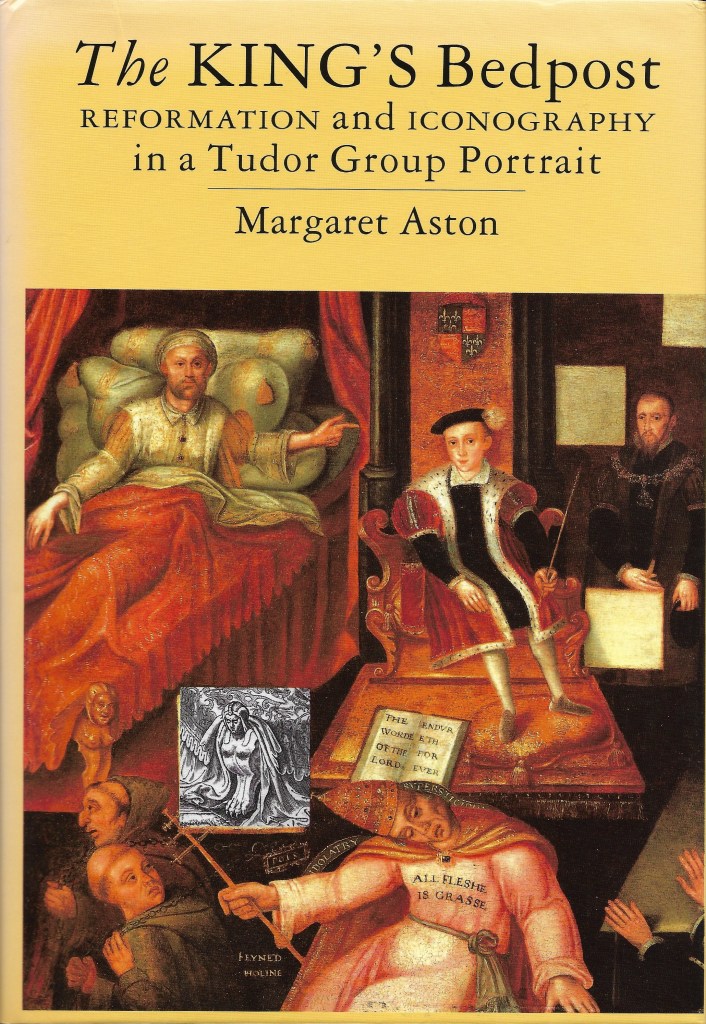

On 30th December 1546 King Henry VIII lay dying, bloated beyond recognition and in excruciating pain from a festering wound on his leg, the result of a jousting accident years before. When his councillors brought him the final revision of his will he was too weak to hold a pen. So the document was signed using the dry stamp, a Tudor version of the autopen which has become so controversial recently. The dry stamp was a mechanism screwed onto paper to make an impression of the king’s signature, which was then inked over by one of his officials. Henry had authorized the use of this device in 1545 as his infirmities grew more severe.

Our current autopen issue is just another of the baseless scandals “trumped” up by President Trump and his acolytes to serve his interests. If autopen signatures on the pardons issued by President Biden can be declared invalid, then Trump is free to charge all his enemies with imaginary crimes. In fact many presidents as far back as Thomas Jefferson, including Trump himself, have used some type of autopen to sign official documents. Jefferson called his Polygraph Machine “the finest invention of the present age.” Richard Nixon, Lyndon Johnson, John F. Kennedy, and many other presidents routinely used an autopen. The question of its legality was definitively answered during the George W. Bush presidency in a 2005 memo from the Office of Legal Counsel. The challenge to Biden’s autopen signatures is unlikely to change history. But the case of Henry VIII’s will was of far more consequence for the history of the English monarchy.

Henry’s complicated marital history and mercurial temperament had necessitated passing three different Succession Acts during his reign. The first two disinherited his daughters Mary and Elizabeth, declaring them illegitimate because his marriages to their mothers Catherine of Aragon and Ann Boleyn were invalidated, by divorce and treason respectively. The third Succession Act of 1543 named Edward, his longed for son by third wife Jane Seymour, as his heir. Mary and Elizabeth were declared legitimate after all and reinstated to the succession order if Edward died childless. If all three should die childless, an unlikely outcome that would actually come to pass, then the succession should follow Henry’s last will. The act included the fateful language that the succession order in his will would be valid if “signed with his most gracious hand.”

Continue reading “The Tudor Autopen”