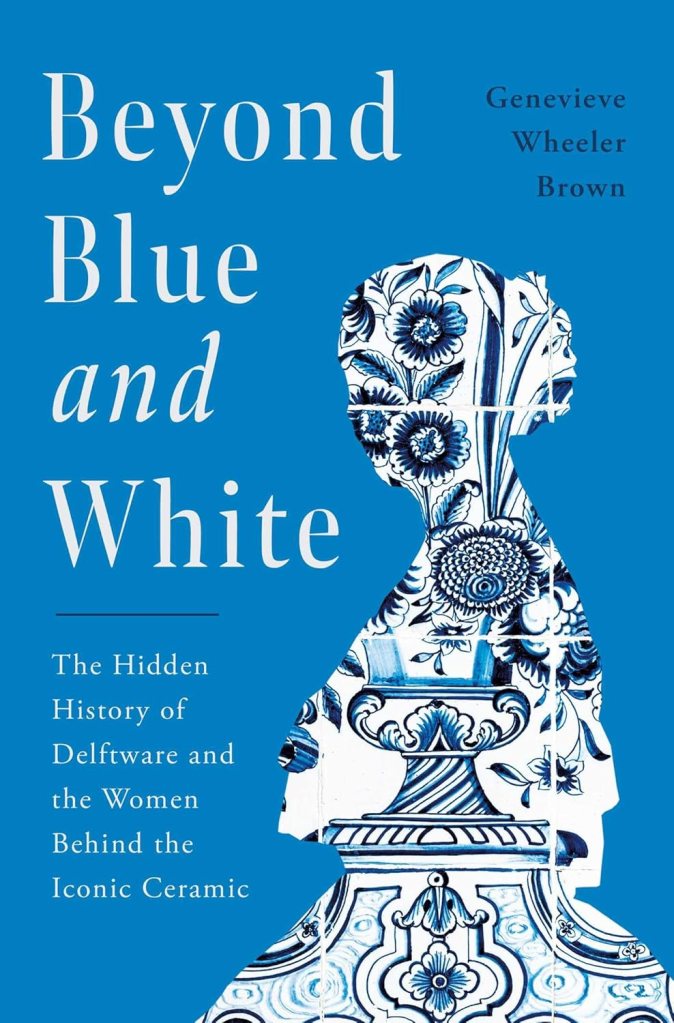

The first thing I want to say about this new addition to my bookshelf is that I absolutely adore the cover. I don’t believe in judging a book by its cover, but I do judge book covers. I follow the Best Book Covers of the Year lists and pass my own judgements on the latest design hits and misses. When will the cliche of the “young woman seen from behind” covers be over? The current fashion is for splashes of garish color and odd images designed to shock or defy explanation. In contrast this cover is an inspired fusion of subject and image. The perfect Delft blue color, of course, and the woman-shaped shard of Delftware have an instant visual appeal and tell the story of the book’s contents – the revelation that many of the famous Delft potteries of the 17th and 18th centuries were owned and managed by women.

Genevieve Wheeler Brown is a decorative art advisor who stumbled on this story by chance when she was asked to appraise a large collection of Delftware stored in the New York headquarters of a women’s art organization. When she stepped into the room, untouched for decades, she was amazed to find a superb collection of over seventy-five blue and white Delftware objects, an overwhelming display of beauty and craftsmanship in a myriad shapes and sizes. This treasure, she learned, had been acquired in the Gilded Age when a fashion for collecting Delftware had obsessed wealthy New York socialites. Brown soon became obsessed herself with researching the history of Delftware.

Continue reading “Beyond Blue and White”

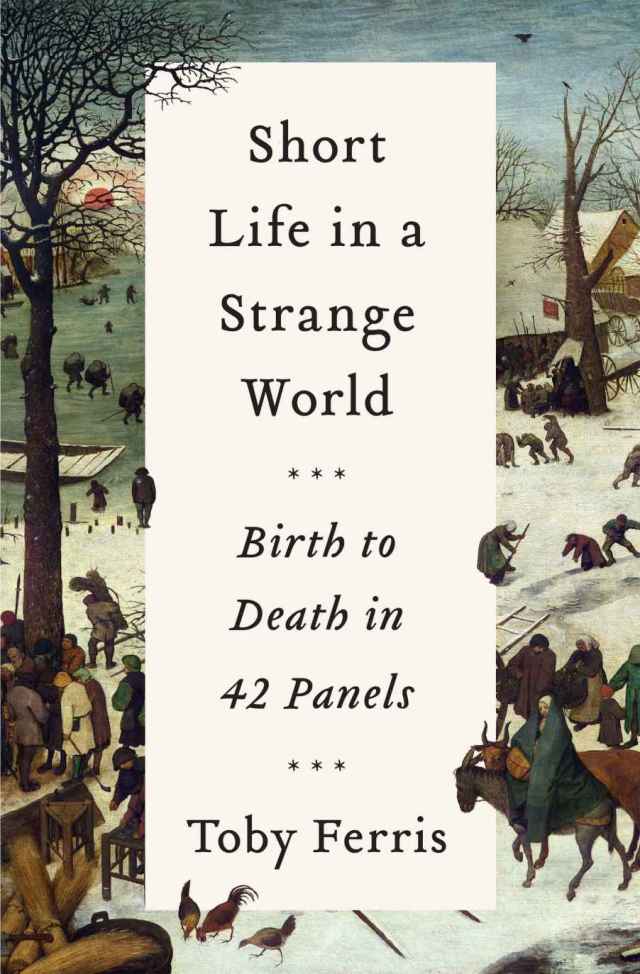

I bought this book on impulse because I will read anything about Bruegel. Perhaps it is my Flemish heritage that draws me to his work. I imagine my ancestors among the peasant crowds in his village scenes. It was only when I held the book in my hands that I recognized the author’s name. Toby Ferris wrote for The Dabbler, the site that first hosted my Dispatches, and he created

I bought this book on impulse because I will read anything about Bruegel. Perhaps it is my Flemish heritage that draws me to his work. I imagine my ancestors among the peasant crowds in his village scenes. It was only when I held the book in my hands that I recognized the author’s name. Toby Ferris wrote for The Dabbler, the site that first hosted my Dispatches, and he created